Pavel Korbička (*1972) deals with light, space, movement and sound in his work. He works with specific places in which he responds to their uniqueness and their hidden orders, which he tries to activate by the presence of the viewer and his individual perception. His artistic activity lies between sculpture, architecture and scientific research. Korbička graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague. Since 1998 he has been teaching at the Sculpture 2 studio at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Brno. In the exhibition at the Telegraph Gallery he presents a site-specific light installation, during the preparation of which this interview was conducted. You can visit the exhibition until 13 February next year.

Your work doesn't quite fit easily into one of the artistic categories. How would you define yourself as an artist, and how do you work?

I certainly wouldn't pigeonhole myself. That's a rather limited way of thinking about the complexity that a work of art contains. However, my means of expression are light and space. I try to grasp space in several ways of approaching it. The ways I have defined are space as a given to be analyzed, then the body as a subject that perceives and experiences space, and the third category is a mutual dialogue based on previous knowledge.

For each new installation it is important for me to know the space perfectly and to create an analysis of the relationships contained within it, which are sometimes not visible at first sight. Sometimes it is enough to draw attention to them with a beam of light. You can talk about its hidden centre of gravity, which you have to hit, and then the space starts to resonate, as it were. You could say that I work with a similar principle as an architect. I'm a kind of architect of light...

As far as the body is concerned, I am aware that we understand space in proportion to it because we are corporeal and we work with the basic principles that are given to us through it. In this category I work with the capture of movement, especially dance. The body will not do the same movement in exactly the same way again. It's hard to say if we are talking about perfection or imperfection, either way we are talking about humanity. Also, the body has its centre of balance. And experience is terribly important, you can't make that up.

The third plane is the product of an active dialogue between body and space. For me, the labyrinthine corridor principle is the third stage of the gradation of the development of my work and it merges the two previous principles, namely working purely with the centre of gravity of space and with the body and the movement of the body in space. The combination of these approaches meet in the installation at the Telegraph, where the viewer directly experiences the movement of themselves within the installation and allows their psyche to influence them. In contrast, calligraphic light installations of movement, for example, can be bypassed, and viewed only from the outside.

Another level then are the audiovisual spatial projects, where I replaced light with sound. In my work, I am aware of my own professional limitations, so I choose to collaborate with professionals in specific fields where my work overlaps. In the case of audiovisual projects I collaborate with the composer and improviser Lucie Vítková, in the case of dance-space recordings with the dancer and choreographer Petra Hauerová, and now, quite recently, with the great Italian dancer and performer Silvia Morandi.

What are the main conceptual starting points of your work?

For me, what is important is what phenomenology has brought. The space we perceive is rediscovered through the body. Thought constructs take on new meaning through it with each new experience.

What exactly can we expect from the Space of Perception exhibition?

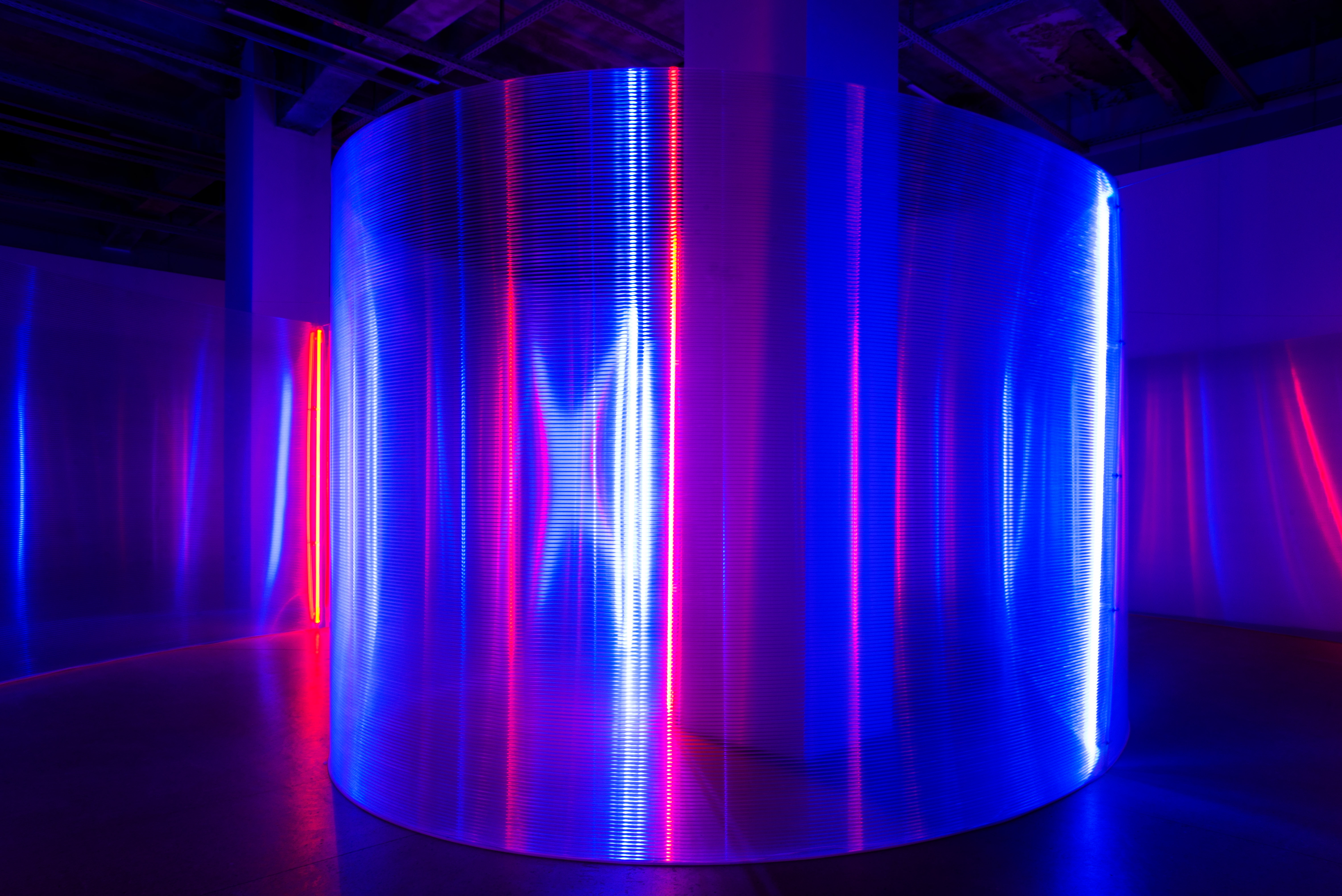

In this exhibition, I present a site-specific installation of a labyrinthine corridor that is a space within a space and is inscribed into the architecture based on a site-specific logic, creating a new reality. I offer the viewer a space that they enter, and through their movement activate certain light moments and phenomena that happen on the curved surfaces of the polycarbonate panel installation. This is studded with light sources at each joint and the material it is made of has the ability to absorb light throughout its volume through a linear structure, but there are also reflections and colour mixing. This results in circular light phenomena that are visible to each eye at a different angle and each hundredth of an angle change dynamically changes its form. We all observe our surroundings through binocular or stereoscopic vision, which is composed of the vision of the right and left eye. The meeting of the two views occurs at the so-called reference point. However, the angled space of my installation and its lighting specifics disrupt this naturalness of vision and a different experience occurs. We see a different phenomenon with each eye and there is an impossibility to find that reference point, and this is a moment of disorientation for the viewer, in which he may, for example, lose his balance or be disoriented in other ways.

Have you ever had someone react negatively to the experience of visiting your exhibition?

Yes. It was an exhibition at the Pilsen City Gallery. It was dark in the basement space and the space was delineated only by light verticals in the form of floodlights, flashing in different ways at different intervals, as if they were running out of life. At the end of the gallery I found a disoriented person who was unable to find his way out of the installation. That was the first moment I realized that my installations could affect someone in such a way. The second moment was at the Biela noc festival in Bratislava, where I was exhibiting a polycarbonate object, and the viewer, whom I was observing going through my installation, suddenly stopped at one point as if he was about to bump into something, which was caused by reflexes flashing in his eyes, which his brain evaluated as an end point beyond which he could not continue.

When I look at your installations, I can't help but compare you to Richard Serra and Dan Flavin. Are these artists a source of inspiration for you?

I don't mind comparisons with these artists as they are big names. A certain distant similarity to Richard Serra is in order, because when you enter his metal installations you become part of an object of incredible size that is slightly tilted, which unbalances you. It's a moment that works with you psychologically in a similar way to my installation, where the moment of disorientation takes place based more on the light and optical situation. And of course Flavin is a great pioneer of light art, and it's interesting to see the transformation of the light atmosphere based on the dialogue of coloured lights. But his works are mostly classical in that they don't transform the whole space, they are like light paintings or reliefs. In contrast, James Turrell or Robert Irwin have already taken a radical step into space and started to explore the perception and behaviour of the viewer within their light installations. For me, Olafur Eliasson or Ann Veronica Jansen are generationally closer, for example, they created light coloured mists inside which it was possible to lose awareness of where the boundaries of our body end. There would certainly be many other artists, such as the Czech Zdeněk Pešánek, whose extraordinary and original nature had to be brought to our attention by the world.

Do you feel that you would like to use other than visual perception in your work?

I've made a few experiments with dance or sound in the past, but I've never been convinced enough to pursue it further. A dance performance or sound within a labyrinthine corridor would have to be free of some kind of artistic professional distortion and would have to be somehow raw. Once you try to make art out of a raw situation, that's it. But I have one sound-space project in my head that unfortunately I haven't had time to work on yet, and I would like to work on it in the future. But I won't reveal what it is yet.

You studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague with Stanislav Kolíbal and Miloš Šejn. How did these two names influence you?

I think I was lucky with my professors in my life. I was afraid to apply to Stanislav Kolíbal, so I applied to Miloš Šejn in his conceptual studio. But he pointed Kolíbal out to me, so I did the second round of admissions to his studio Sculpture - Space - Installation, where Jiří Příhoda or Petr Písařík, for example, had already studied. I remember that Professor Kolíbal had an incredible ability to rationally analyze space and work, and he was able to open up in me a sense of considering this work within a broader spatial context. In contrast, Professor Šejn, to whom I turned to study after Stanislav Kolíbal left the Academy of Fine Arts, encouraged a different sensibility, connecting other levels of meaning, and sparked my fascination with the movement of the body in space. I started to collaborate with students of the Duncan Centre in Prague, and some of them are still collaborating today.

How does the teaching activity in the Sculpture Studio at the FaVU BUT influence you, and what do you think about the division of the studio by media? In your opinion, is it an outdated concept?

For me, it is interesting to have a discourse of ideas with the younger generation and I hope it is mutual. If it's not about being aggressive but mutual tolerance, characterised by passion for the cause and trying to get to the best outcome, then it's mutually charging. My endeavour is to understand the mindset of any individual who shows interest and to help them open up the potential that lies dormant within them, or conversely to unlearn the learned mannerisms in which they have become stuck. Often it can be a matter of closing oneself off into "bubbles" in which they feel comfortable, and partly why their work is quite subjective. In terms of the distribution of studios, I think they should cover as much of the disciplinary spectrum that resonates with the context of contemporary art. And I think it's better to stick to disciplinarity than to bend the content of the studios according to the teachers, because that can make the studios too similar in the small Czech pond.

The title of the show refers in part to the exhibition Event of Space that you had at Caesar Gallery in 2013. Do you feel any connection there?

The title of that exhibition, curated by Miroslav Schubert, was based on a text by Miroslav Petříček, who described my installation at the Via Art Gallery in Prague in this way. Simply put, "the event of space", because the space of the installation, which the viewer enters, happens together with him. The viewer, through his active movement, participates in the creation of visual light events that accompany him until he leaves the installation. If he does not move, he sees only half of what he could. Children especially love this. Until then, it's similar. But the Telegraph will be an installation spread across the entire gallery space, splitting it in two and causing viewers to pass and perceive each other only through vertical light barriers. However, the installation and the deflection of the psyche may be uncomfortable for some.

You have had many exhibitions not only in the Czech Republic but also abroad. Are you planning any other foreign exhibitions?

In early November I opened a long-planned solo exhibition at Villa Cernigliaro in Sordevolio, Italy, curated by Miroslava Hajek. The exhibition will be on display there until the end of January next year. This is an extraordinary historic space in the villa, which was an important centre of anti-fascist resistance in Italy during the Second World War, and now serves as a cultural centre, hosting exhibitions that are locally specific to this unique space. In my case, these are sensitive interventions of light and colour in this remarkable architecture with its historical patina and memory. But I am also planning an exhibition next year at Berlin's SCOPE BLN gallery, where I was an artist in residence two years ago and realized a permanent light installation in the entrance of this residence. It can be visited at Lübecker Straße 43.

Do you have any places in the Czech Republic where you would like to realize your project?

I would be interested in the Troja Castle in Prague, for example, which is part of the Prague City Gallery and has great spaces. Their long-term concept is to work with reactions to the historical space of the castle. For example, Vladimír Škoda or Jiří Příhoda exhibited there. In addition, I would like to do an installation in non-archival spaces such as the Church of St. Salvator in Prague or St. Wenceslas Cathedral in Olomouc. The principle of contemporary art entering historical sacred spaces is not so common in the Czech Republic. But the situation is different in the world. In Milan, I have seen installations by Michelangelo Pistoletto, Tony Cregg or Lucio Fontana in sacred buildings. These are often radical approaches, but they resonate well there.

But I would also be interested in exhibiting in a hitherto non-existent Czech gallery designed by a contemporary top architect on a green field as a perfect space unencumbered by its own artistic ambition, without being a modification of a building originally built for another purpose.

The polycarbonate panel installation at Telegraph Gallery is variable, having been exhibited in various guises for several times, but it evolves, responding to each space in a different way. What exactly is this evolution?

I'm working with a prefabricated module. This allows me to build spatial building blocks based on the site specifics of particular galleries. With installations as large as the ones I create, there is perhaps no other way to do it. The first installation of this type took place in 2003 at the Moravian Gallery in Brno. Initially, however, it was a work with closed forms that could not be physically entered, at most between them. Gradually, however, I am opening up the forms of the installations to the viewer so that he can enter inside and experience the most important thing - the manifestations of his own body and through them his own story. I wanted to work with open form for the first time in a group exhibition at the Václav Havel Airport in 2008, but unfortunately this type of installation was not allowed there because of the gathering of homeless people. We could only anticipate the internal modelling of an otherwise cylindrical object, but we could not be part of it.

The fully open form was only successful in the Liberec gallery Die Aktualität des Schönen in 2010. One entered the gallery, and at the same time one also entered the installation. However, the last type of installation realized in the Telegraph, in contrast to the one in Liberec, works with two entrances. We can walk through it without having to return.

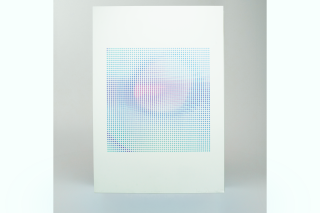

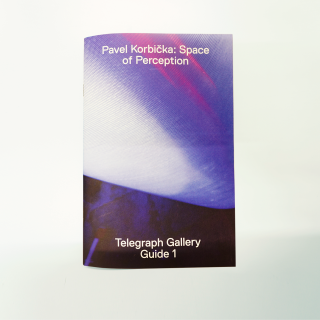

For the occasion of this exhibition, Pavel Korbička has created a serigraph for the Telegraph Gallery. Its subject refers to a motif that the viewer encounters immediately after entering the installation. It is a dynamic light pattern, broken up into regular points, which creates a visual tremor and is a metaphor for the optical experience inside the installation. In addition, an exhibition guide was also created. Also available for purchase is a author's catalogue and the book Spaces, which is a collection of the author's texts that discuss the theme of space from the perspectives of fine art, architecture, design, music, literature and philosophy.

All available on our eshop.

By Mira Macík / Telegraph Gallery