Nikola Emma Ryšavá (*1990) is a graduate of the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague, where she studied sculpture in the studio of Lukáš Rittstein, which she got to through studying ceramics and design of wooden toys. Ryšavá's work is characterized by surreal elements, often frightening, but also grotesque or emotional anthropomorphic figures, which she often performs on a large scale. The themes of the sculptural works are based primarily on the inner world of the artist herself, her interest in psychoanalysis, but also on literature. The desire to capture what goes on inside a person is one of her major themes, as well as intimacy and interpersonal relationships. For the sculptor herself, art-making is a form of therapy. Nikola Emma Ryšavá has already had a number of exhibitions, for example in the industrial hall of Prague's Vnitroblock. Every year, she also participates in the VáclavART art project, which aims to stir controversy through works placed in public space, to spark discussions about the shape of Wenceslas Square and its revival. However, Ryšavá has presented her works not only in many exhibitions in the Czech Republic, but also abroad, for example in Italy, Portugal and Australia.

How was your journey to the Academy to Lukáš Rittstein's Sculpture Studio and how do you remember your studies?

It was a longer journey because after high school I wasn't sure what kind of art I wanted to pursue. Before I started studying sculpture, I did a degree in wooden toy design. It was a nice diversion and I think the experience has positively influenced my future sculptural work, which is occasionally playful. It was while studying design that I finally realized I wanted to pursue sculpture. So I enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts in the Studio of Sculpture I, which at that time was headed by Jaroslav Róna. Although Jaroslav Róna accepted me into the studio, he never taught me personally because he left the Academy that year. The studio was taken over by Lukáš Rittstein, who ran it brilliantly. If you worked hard as his student, he gave you great freedom to express yourself in your work the way you wanted. That suited me fine. I remember the Academy quite fondly because I had the opportunity to learn many things there, especially in terms of technological skills. It was also great that I had the opportunity to study abroad, which I took advantage of enthusiastically and studied in Australia and Portugal.

You also work with the female character in your work. How do you perceive women in art? Is she a big theme for you?

Originally, the female figure came into my work kind of naturally, because I was mostly processing my own experiences. Later I started to focus more on the woman, as such, when my work became more feminist. I am aware of my good fortune to have been born in this time, in Central Europe, and to have had liberal parents who allowed me the freedom to choose my artistic career. Unfortunately, many women in the past did not have that freedom.

When did your interest in psychoanalysis develop? Why did you decide to leave reality behind and reach thematically more into the inner world and mysterious mystical figures?

My amateur interest in psychoanalysis began about ten years ago, and remains close to me to this day. It is widely known that artwork often acts as therapy for artists, and for me it is no exception. Therefore, I decided to deepen my knowledge of psychoanalysis and understand its concepts. In doing so, I wanted to discover new methods to best express inner worlds in my art. Of course, reality also has its place in my work, but sometimes it is necessary to break away from it in order to keep one's creativity and not go crazy.

Can you tell us what other literary works have influenced your work?

For example, the book The Virgin Suicides by Jeffrey Eugenides. The whole narrative of this book tries to reveal a certain "truth" behind the story. In The Virgin Suicides the author uses an "unnatural" collective narrator. The source of the story is not "I" but "we." The fact that the individual members of the group are not clearly defined contributes to the unnaturalness of the narrative technique and the portrayal of the group functioning as a separate entity. This book inspired me to create sculptures in which I worked with text and also used multiple voices and a collective narrator.

Working with a range of materials, which do you feel closest to?

I am closest to textiles, which make up a large part of my artwork. Textile is obviously not the most practical material for a sculptor, so I combine it with fiberglass, in which I "bury" the textile, or conversely, I use textile materials to cover sculptures that I cast in plaster molds, which I then cast in concrete. The resulting product then looks like a soft and flexible textile, but is actually stable and strong.

You are regularly involved in the VáclavART art project - which seeks to provoke controversy through the engagement of art in public space. Do you think that art in public space can have a greater impact on people who pass it by and who are otherwise less interested in art? What role do you see for art in public space?

Exhibitions in public space are my favorite and I consider them my most important. The number of people who see sculptures during exhibitions in places like Wenceslas Square, Prague's embankment or in the various city parks where I have exhibited is absolutely incomparable to the number of people who come to exhibitions in galleries. I usually enjoy the reactions of the "general public" and often hear much more interesting opinions than from the typical gallery audience. Art definitely belongs in the public space, and I'd like to see a lot more of it around me. I consider any attempt to wake people up out of their apathy to be a positive thing, and art in public spaces can definitely influence people, even if it's just for a moment to maybe wonder what weird work they're seeing, it's still worth it.

Often your work is quite controversial. Are you happy for them to provoke intense reactions?

My works are not controversial by design, and I don't consider them controversial at all, for example, but I admit that they often provoke strong reactions. Especially when they are exhibited in a public space. The audience often reacts to them either with enthusiasm or, on the contrary, with great reluctance. I prefer these stronger reactions, they are better than if my works bore people or leave them cold. In any case, I am not upset by negative reactions. I'm my own biggest critic, so if I'm happy with a sculpture, it doesn't bother me at all that others might not like it. It's impossible to please everyone, so I don't try to do that.

You've also shown your work abroad several times. Which exhibition do you like to remember?

For example, the first one abroad in Milan, the Andante exhibition, was very good. Or the last exhibitions abroad, in the beautiful surroundings of the Czech House in Brussels and in the industrial spaces of Warsaw.

You're currently doing a residency at the Telegraph. How are you finding working here? And what works will we see in the short-term exhibition on October 13?

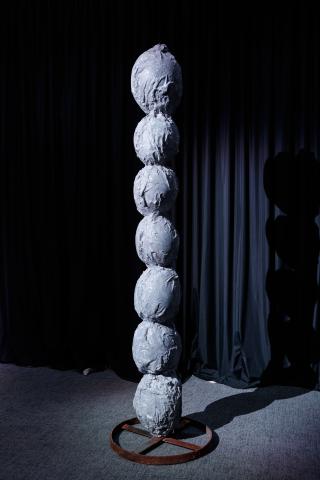

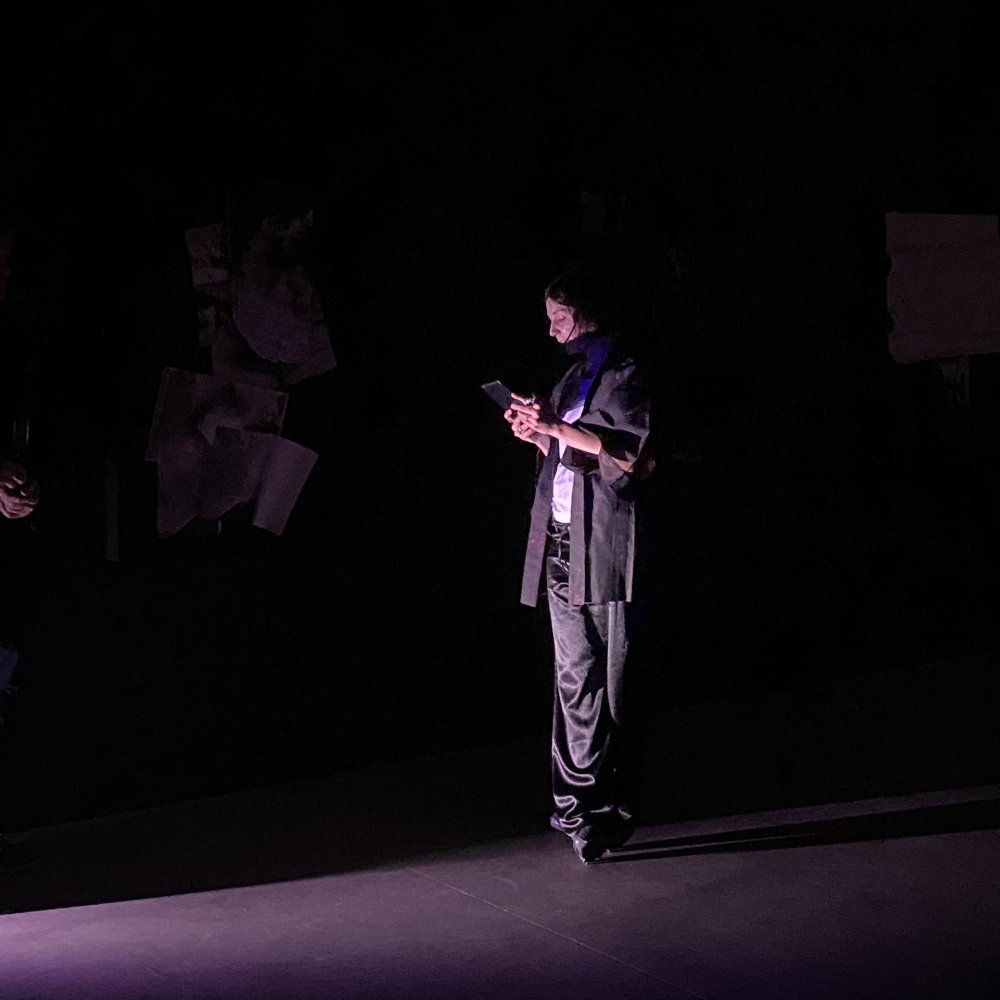

I'm having a good time working here, no one disturbs me too much, which allows me to be even more productive than I am back home in Prague. I have already created several new works here. Living right next to the studio is an experience I'm having for the first time, and it allows me to work almost non-stop. This is a great advantage during the two months of residency. However, in the long term, such a deployment would be unsustainable. This year, I naturally gravitated to the most famous vertical sculpture - the column. Plague, Marian and memorial columns are characteristic of Bohemia, and almost no other country compares to us in terms of the number of columns and loose sculptures in the landscape and in cities. The columns were erected as thanksgiving for the outbreak of the epidemic and usually also as a plea to save the place from further misfortune. It is during my time at the Telegraph that I am working on my own interpretation of the 'pillar of our time'. I am trying to capture my ambivalent feelings that the current times evoke in me. My column sculptures will be accompanied by two larger figurative works - Wolfman and Dispelling the Disguise. Wolfman represents the figure of a man trapped in the body of a wolf, while Dispelling the Disguise depicts a demon who is in the process of removing his human mask.

What are your plans for the next year? Are you going to travel anywhere?

I have a few more shows planned for next year, I currently have a few group shows confirmed and at least one solo show. At the same time I would like to combine my artistic activities with another residency, this time abroad. I would be most excited to have the opportunity to do a residency in Japan, but I will have to find the most suitable opportunity. I plan to build on my previous work, which has been inspired by the treatment of folklore as a historical memory of place. I would like to explore the contrast between Czech and European vernacular and Japanese culture.

By Barbora Langová, Inka Ličková / Telegraph Gallery