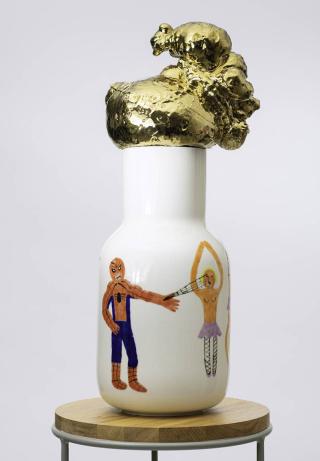

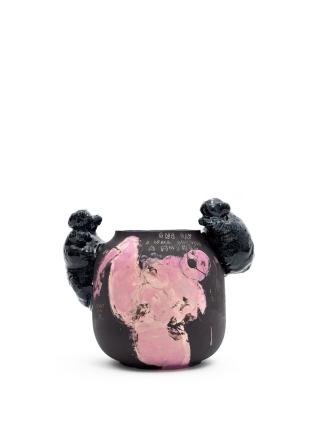

Zuzana Svatik (born in 1993) is a Slovak visual artist who specializes in ceramics. In 2018, she completed her master’s degree at the Department of Ceramics at the Academy of Fine Arts in Bratislava. Her work focuses primarily on ceramics, drawing and painting, and critically explores the function and potential of applied art in contemporary society. In her work, she addresses themes such as gender equality, stereotypes and identity, and often reflects on social and gender prejudices in Eastern Europe. Her artworks are not just functional objects, but serve as a platform for dialogue about social norms and values. Zuzana Svatik soon gained recognition after she received the Collection of the Year Award at BADW in 2016 and two years later, the BADW Main Prize for her project "Miksmitte." This interview was conducted on the occasion of the exhibition of Zuzana Svatik's work at the Telegraph Loft.

Your work focuses on utilitarian objects and their potential to reveal hidden stories of the household. How do your personal experiences influence your work? Have you ever depicted a specific story from your life?

I wouldn't say I reveal "hidden stories of the household." In my work, I am primarily interested in the practical isolation of the nuclear family within the modern household, which creates a space where psychological and physical violence, stemming from normalization and repressive practices, is reproduced in isolation from broader society.

As a bearer of conservative Christian values embedded in an environment of patriarchal neoliberal capitalism, my family has undeniably influenced me in fundamental ways. If the residual effects of repressive practices in society are applied unsystematically to me as an individual from an early age, and at some point my family began to “support” me in my artistic practice, it’s questionable to what extent this is “support,” and to what extent it is a tendency to redirect energies in a way that will not disrupt the conservative household environment.

My childhood and adolescence probably cannot be separated from my work, nor have I ever tried to separate them in the first place. I also don't know what kind of person I would be today if I had grown up differently. I find it irrelevant, it's like wondering who I would have been if I’d grown up in the North Pole.

You're currently experimenting with large-scale ceramic objects. What challenges and opportunities does this format present in terms of technology and functionality?

I find working with utilitarian objects, as I’ve done in the past, to be exhausted and denounced. I am currently engaged in creating loose objects and figurative compositions that challenge me conceptually and technologically within the ceramic medium. I find this transition natural, but at the same time this departure from my comfort zone is quite nerve-wracking.

You also depict religious motifs. What is your personal relationship to these themes, and how do you connect them to feminist and gender issues?

As a child, I went to church, was baptized, and had my first communion. I was unable to receive the Sacrament of Confirmation, by the age of fifteen, my separation from Catholic teaching was sealed for good. In the early days, it was likely a rebellion against the Church and tradition itself, which may be linked to many of the negative aspects that still survive under its guise. The adjective "traditional" in the context of Christian teaching, which in our society represents the only "correct" code of morality and existence, means nothing other than "order at all costs." It is significant that even today, the nuclear family with its conservative and Christian values still represents one of the ideals promoted by fascist ideologies.

I remember when my sister, thirteen years younger than I am, was enrolled by our parents in religious education, I read in her textbook that she should only touch her body minimally and only if necessary, for example during evening hygiene. In my work, I also observe the ways in which Christian teachings distort the perception of and relationship to one's body and sexuality.

I don't think that the "will of God" should be applied as a general moral principle, especially in decisions with societal impacts, such as those regarding reproductive rights.

This doesn’t mean I see spirituality as negative. Rather, I object to patriarchal religions dominated by men and to Western metaphysical dualism, which underpins forms of group oppression, itself formed on Judeo-Christian religious principles.

The way I portray these themes may sound ironic, as their interpretation can have multiple layers.

The current political situation in Slovakia is not favourable to art. Have you recently been influenced by any particular political event that you would reflect in your work?

Politics today has become a commodity that we are compelled to consume. In the media, political content is presented for the sole purpose of evoking as much negative emotions as possible, which is an easy guarantee of profit. It works very well—it is rare that political events don’t evoke anger, disappointment or disgust in me. This inevitably translates into my work. I am interested in art's ability to reframe perceptions, destabilize existing systems and political structures, and openly criticize current events; in this sense, it is essential to my work.

In parliament, men decide on women’s bodies, and if they can even formulate a meaningful sentence, it is rarely based on anything other than God’s will. Sexism and the public humiliation of women, LGBTIQ+ individuals, and minorities are seen there not as something negative, but as an expression of masculinity and a tool of normative power, and the crowd applauds it enthusiastically. Such primitivism and profanity are so pervasive here that it threatens to become the norm.

If you ask about the situation of culture in Slovakia, I’d say that the field of art and culture has been systematically unsupported since the Slovak Republic’s founding. However, thirty-one years obviously had to pass for us as a society to notice this, and an incompetent minister with an openly fascist mindset had to take office, spreading hatred, polarizing society, and disregarding human rights.

The appropriate question is therefore not whether something should be changed, but rather if anything should remain unchanged.

You lived and worked in Berlin, a city known for its open and progressive art scene. How has your stay in this city influenced you as an artist, and what differences do you perceive between the Berlin and the Slovak art scene? Was it too much of a shock to return to Slovakia

Returning to Slovakia is always a big shock, even if I'm only away for a few days.

Regarding Berlin’s art scene, I would say that its unconventional, vibrant, and progressive character is a product of the city’s open and free culture. The conformist mindset of much of Slovakia’s art community, combined with the absence of alternative spaces to institutions and buy-sell galleries, does not create a positive environment for artistic expressions that challenge these norms.

I returned to Slovakia because I was heartbroken. During this period, I chose to focus on theoretical studies and pursue a Ph.D. However, I believe that I will leave here soon.

What developments do you see in your work in the future? Are there any themes or forms you would like to explore?

During this academic year, I would like to finish my Ph.D., which is tied to the completion of the theoretical part of the thesis and a presentation of the practical part. I plan to divide my work into three sections: an exhibition of a cross-section of my work over the past three years, an outdoor fountain in a public space, and an installation in a gallery space, which I plan to transform into a swimming pool with complex ceramic sculptures. After this output, I would like to leave this nationalistic state.