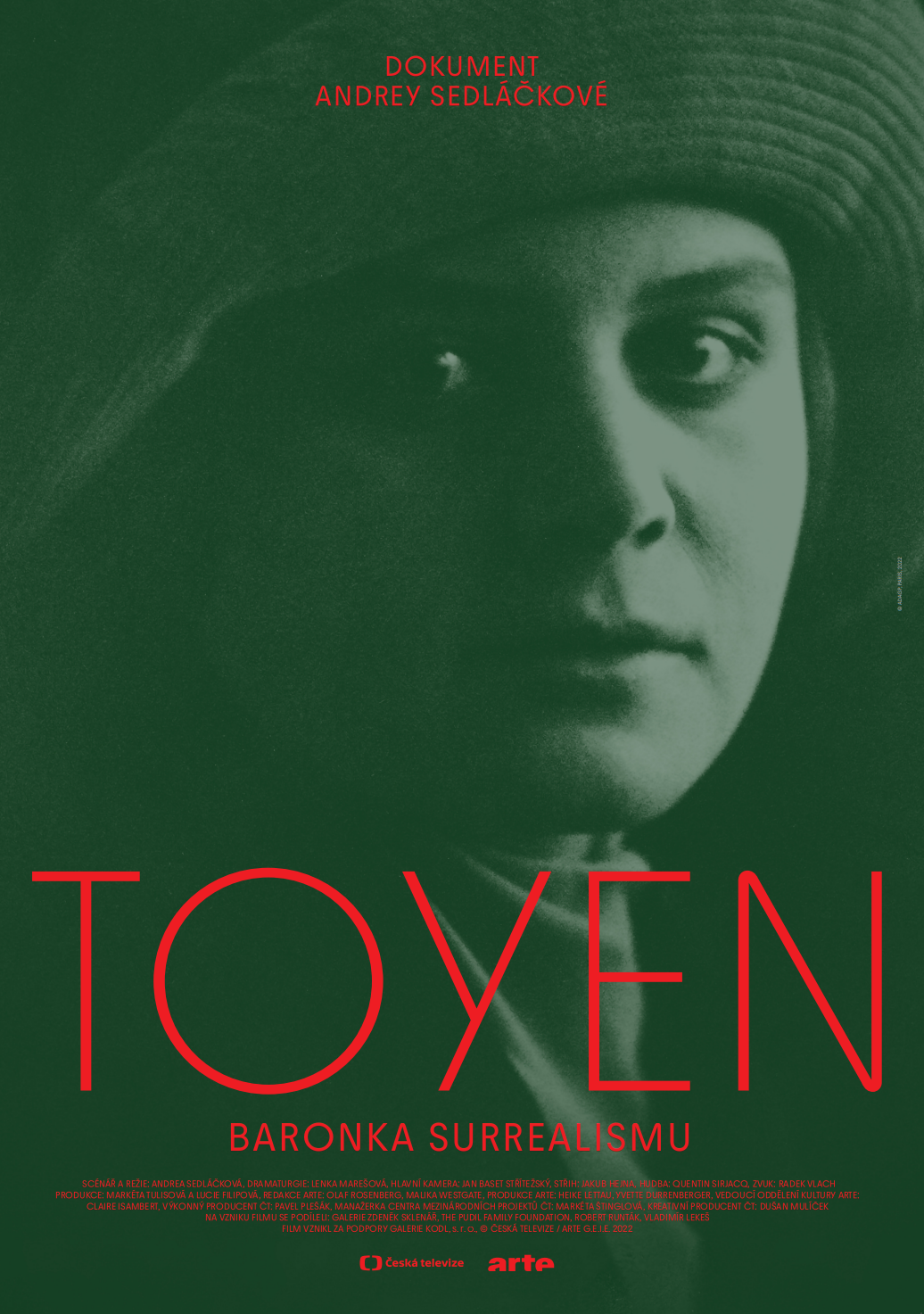

In the second edition of the Telegraph Film Festival, the new documentary TOYEN, THE BARONES OF SURREALISM by Andrea Sedláčková is being premiered here. The film, co-produced by Czech Television and the French-German ARTE, has not yet been seen in cinemas despite its original planned release. Telegraph also financially supported the film's creation and on 28 October TEFF audiences will finally be able to see it on the big screen. The documentary portrait captures the painter's entire life and work and allows a glimpse of previously unseen paintings. In addition to the screening of the film itself, we also present an interview with the award-winning director.

Do you go to the cinema to see documentaries about the visual arts?

Unfortunately not very often. Last time I saw a film about Alfonso Mucha in the cinema, but otherwise there are not many films about artists in the cinema.

Do you think the audience should see your film in the cinema?

The making of Toyen was such a combination of happy and unhappy accidents. In 2020, I was approached by Czech Television Brno, which wanted to make a classic documentary based on a combination of images and interviews with art historians on the occasion of a large travelling exhibition of Toyen between Prague, Hamburg and Paris. But I thought that Toyen is a really huge subject, that I would like to conceive the film in a generous and different way. I came up with the idea that the paintings should not be talked about by the people whose job it is, but by the people who live with them. My concept of reaching out to collectors seemed like a very complicated thing at first, because in the Czech Republic most collectors don't want it to be publicly known that they have Toyen paintings in their homes, representing quite a considerable fortune. Although in the end there were a few brave ones, just like in France. In Paris, I also managed to find several personal friends of the painter, whom I had not counted on at the beginning, but it seemed like a documentary duty to record the testimonies of these people. And above all, the memories are very interesting and valuable! Of course, I thought the project deserved a film screen. As the date of the grant for the development of the cinematographic work was approaching, we put together the materials at the last minute, but unfortunately we didn't get the grant. This could also be due to the fact that the current grant committee generally doesn't consider documentaries of this type, or rather classic films, to be very interesting and focus more on social issues, minorities, gender, etc. However, the French-German ARTE entered the TV co-production and thanks to their financial contribution we were able to shoot in France, which was essential for the film. We conceived the film with the cinematographers for the cinemas, and Bonton was interested in distributing it in their cinemas, but in the end we decided not to go down this route, which ran into various problems of premiere dates. It has to be said that even if the film were to be officially released in cinemas, its form would not change significantly and it would of course be nice to see it in cinemas, but at the same time it is clear that at most a thousand people will come to see this type of film. I felt a certain regret when I saw the film on the big screen at the gala screening at the French Institute. I realised it was far more impressive.

You've made a number of documentaries and portraits, and here you go the furthest back yet. How was working on this film different for you?

We work extensively in the film with archival footage in addition to interviews. I tried to find the "unglamorous," which is what the Archive of Private Film History, which collects amateur period footage, was useful for. This is where the unknown footage of pre-war Prague and Paris comes from. Also, thanks to ARTE, I was able to use beautiful French film archives that would otherwise have been beyond our financial means. I also found the only film footage of a "live" Toyen from the 1960s. The next nut to crack was the photographs of Toyen herself, of which there are not many. However, I did manage to discover, after much searching, several unpublished photographs. Another problem was the rights to Toyen's paintings. In order to film any image, you must have the permission of its current owner. But they are often hidden in anonymity and very difficult to identify. Consequently, you have to pay AGDAP, which is bribing her heirs, quite a large sum for any Toyen work, even a simple drawing. 250 euros per piece. So I knew from the beginning that our budget would only allow me to present forty works.

The title of the film, "The Baroness of Surrealism", refers to the painter's nickname from the Parisian art scene. Was this the intended subtitle from the beginning?

No, the film was originally called Mysterious Toyen, which, while one of the most typical adjectives for the painter, is also one of the most banal. But the title, for me, related to the concept of the film, built around a search for Toyen's past and the uncovering of unknown information. In the end, we found "The Baroness of Surrealism" far more interesting. As one memoirist tells it, the Surrealists called Toyen the Baroness, though of course she was no aristocrat, but she had a nobility of spirit.

The film was edited by Jakub Hejna, a leading Czech documentary editor. When the film was made were you in agreement about what would appear in the film? Is there anything that you regretted that did not make it into the film?

With only three weeks in the budget to work in the editing room, Jakub and I knew that, in addition, we had to produce three different versions during that time, one short Czech and French version and one longer version of 15 minutes that was planned for the cinema. This kept us under considerable time pressure, so there was no time for any deep and long discussions. I would always prepare a script before coming to the editing room based on the footage, which was about thirty hours long, select the best contributions and shots, time code them, pre-prepare all the archival period material, photographs and send everything to Mr. Hejna's assistant who would prepare the material for him. And then we go like a factory. We both knew what we were getting into, because this was not our first collaboration with Jakub, and he is intelligent and bright, so he then edits a poem from my pre-selection. I'm also an editor by profession, which perhaps makes the collaboration easier. And every evening when I came back from the editing room, I recorded the Czech commentaries at home, which I continuously edited according to the development of the editing and translated them into French so that the French producers could understand the commentaries during the approval process. I also had to translate the Czech interviews into French and the French interviews into Czech so that all the co-producers of the film could understand. It was a huge job. To answer your question if I have any regrets. Just that more of the Toyen paintings I shot didn't make it into the film because they are largely from private collections, so Toyen lovers can't see them right away. Of course, they can look them up in catalogues or find reproductions on the internet, but their plasticity is visible in the film, and I tried to shoot many of them with collectors in mind, so that you can see the actual dimensions of the paintings, which adds to the impact of the work.

The film features several experts, collectors and restorers, as well as friends of the painter. How did you approach them?

The Kodl Gallery, which has been dealing in Toyen works for many years and knows all the Czech collectors, was very helpful to me. And also Dr. Karel Srp, who is one of the greatest Toyen experts and who recommended me to French collectors. They have great confidence in him, without his help they would not have talked to me. I was preparing the film in the spring of 2021, during the third wave of covid, and at that time these people, who are usually quite unavailable for work reasons, were at home, bored and made time for me. Gradually they recommended me to other collectors and the same went on with Toyen's friends. I found the first person through a friend and they recommended others, etc.

With Toyen you share that figurative straddle between Prague and Paris, where you alternately live and create. How does the view of Toyen differ between the Czechs and the French?

Diametrically. In our country, Toyen is a star who regularly breaks records in auction houses, so it's well covered in the newspapers and even people who are not that interested in fine art have at least some awareness of Toyen's existence. In France, Toyen is still, as one of the characters in the documentary says, somewhat forgotten, although her work is gradually finding its way into the leading galleries. But sporadically - the artist's paintings are so far only in Paris, Edinburgh, Stockholm, Vienna, Bochum, Tel Aviv and Qatar.

Do you see any other themes emerging in your film through Toyen's life?

I'm currently writing the Toyen biopic because I gathered a ton of new information during the preparation and filming of the film that I couldn't fit in, and I continued my research after the film was finished. Symbolically and physically, I knocked on doors that hadn't been opened and discovered a lot of really interesting things.

For example, on the subject of Toyen's sexual orientation?

That's such a primal cliché that I naturally had to work into the film, so I gave the floor to the only art historian who appears in the film, Martina Pachman, who specialises in sexuality and gender. The painter's masculine style of dress and boyish hairstyle is notorious. But if you start to study a little more, you see that dressing in trousers was related to her involvement in an anarcho-communist group and didn't last long, and the short hairstyle was fashionable in the 1920s. Toyen's friends tell me that the painter liked feminine beauty, but they don't think it went any further.

Did you find a favourite image in the artist's work?

I admire her art fiction period, which also has various sub-periods, and the one I am closest to is from 1930-31, when she painted images that were colourful, optimistic and suffused with life and beauty. One of them is Flower of Sleep, which you can see in the Olomouc Museum of Modern Art!

In the introduction of your film you work with a series of different adjectives to describe Toyen's personality and work. What adjectives would you use to describe Toyen?

Do you mean to her character? That's interesting, I asked people exactly like that when I was filming and those who knew Toyen personally automatically talked about her character and collectors talked about her work...I would say - opinionated, unconventional. And affectionate....

Toyen, The Baroness of Surrealism

28 10 2022 17:00

BUY THE LIST

TELEGRAPH FILM FESTIVAL

26 - 29 10 2022

ACCREDITATION and PROGRAM

By Michael Bukovansky