When I was a child, in the 1980s, I often had a dream: I would walk through the staircases and hallways of our block of flats and discover unexpected nooks and hidden corridors leading to another, remarkable world. Around these corridors hung tapestries, the walls were rhythmically adorned with curtains, and various alcoves, columns, cornices, and other elements resembled architecture (or at least historical architecture). The actual view of my home environment (that is, the interior and exterior spaces of a housing estate) was significantly poorer. Often it seemed to me that everything was so “clear” that there was nothing at all.

Completely straightforward, grey blocks of flats, geometrically designed playgrounds made of metal tubes, at the edge of the estate, two grocery stores, two pubs, a blue pavilion housing a library and a hair salon, and at the opposite end of the estate, two large complexes of elementary schools, and a civic amenity site, leading towards the forest.

Every path and every corridor was entirely predictable; they didn’t veer off to the side, leading precisely to a classroom, a pub, or a phone box. The moment of surprise, the experience, the mystery? Almost a complete zero. I understand that the role of urban planners and social strategists cannot be to create convoluted mazes. However, the opposite extreme, a kind of basic utilitarianism, produces such an intense sensory and emotional desolation that it inevitably leads to an effort to create one's own so-called “islands of positive deviance,” perhaps in the realm of recession, quasi-rituals, and so on.

A well-arranged, easy-to-navigate world can seem like an ideal solution to various existential problems (idyll, utopia, etc.). However, it does not allow for a more complex and diverse experience. When we then transition from such an environment, resembling a game board for “Ludo”, into worlds more akin to “Star Wars”, misunderstandings may occur. There were several types of visual culture in public space in the 1980s (official, promotional, wayfinding systems, DIY attempts at decoration, or whimsical embellishments created from below, etc.). This visual culture had a remarkable characteristic compared to today: it was disappearing. Posters in the windows of convenience stores and other shops were yellowing and fading, while decorations that had not been replaced for years were vanishing beneath a crust of dust and dried insect bodies. Facades were covered by rusty scaffolding, seemingly aspiring to enter the Guinness Book of Records for endurance. Political and commercial advertising, decorations, and signs—were fading, rusting, yellowing, and crumbling, thus acquiring a distinctly authentic patina. The ravages of time, even with their poor visibility, were unmistakable. It was intriguing to observe whether things were the same behind different fences. At least the boundary of the fence evoked a sense of the unknown. A crack, a crevice in the middle of a scratched wall—a glimpse behind it could have been one of the greatest imaginative adventures (there was a neglected garden).

This essay aims to weave together and compare three perspectives on the “eighties”: personal experience, historical context, and the prism of contemporary artistic reflection. For the purpose of this text, personal experience and memory have been kindled and somewhat enhanced by photographs from the family archive (mostly taken by my father). The relatively poor technical quality of these photographs speaks volumes about the visual culture of the time and its limitations (common photographic materials—films, papers— were then limited to partial visibility). Similarly, the overall visual culture of the observed epoch had relative possibilities that, nonetheless, provoked a correspondingly stronger imaginative response.

I. The Blocked View

The experience of a certain invisibility or emptying of the visual field in public spaces corresponded to the basic rhythm of daily activities and the fundamental structuring of time. Time was divided into a kind of ordinary and extraordinary routine, with an almost impenetrable boundary between them. For experiences of novelty or difference, one had to escape beyond the realm of everyday routine—to cottages, gardens, collecting hobbies, or to allied seas, where the gaze was then nourished by artutilitarian, and thus somewhat aesthetic, phenomena.

This sense of invisibility within the everyday routine is exemplified by two staged photographs by Václav Stratil. In one, the artist is shown with his eyes closed, with the word “BOREDOM” crudely written on his forehead. In the other, he appears with spoons over his eyes—coffee spoons, to be precise. A coffee break might have represented a small shift, a micro-event that interrupted the regulated flow of the mundane. Similarly, Květa Válová’s paintings embody this everyday limitation of the visual field through their emphasis on immobility, heaviness, and shades of browns and greys. Patina, as the trace of time, plays a key role here. Grey becomes a distinct theme or artistic strategy. The East German poet Detlef Opitz once made the following observation about the city of Halle: “and then one might be lucky enough to discover the charm of this city of grey, morbidity, transience; precisely the charm that makes this city so repulsive.” Grey appears ordinary, poor, and ascetic, suggesting both decay and moderation, nobility, and taste. This is how grey also manifests in the paintings of Petr Veselý, filled with traces, stains, and blurring. This colour reduction not only comments on the uncertainty and restriction of vision but again implies the relics of time. We also encounter the grey spectrum in many works from that period by Vladimír Kokolia and Jiří Kovanda, showing two versions of the “blocked view.” It’s either an empty or a convoluted, impenetrable visual field: Kovanda’s reverse of the canvas versus Kokolia’s labyrinths; a coiling into oneself like a shell in Marius Kotrba's paintings, versus the light traces, almost imperceptible folds and wrinkles in the works of Adriena Šimotová.

The view could be blocked by constructions, scaffolding, and concrete housing blocks, behind which nothing is hidden—no authentic, non-predestined path for the gaze or life (as exemplified in the paintings of Vladimír Novák). In Jiří Sopko’s painting, we even see blocked ears (as if they were connected and deafened by a "radio on a wire") along with improbable joy, a grotesque quality reminiscent of the family outings of the Homolkas (as in the 1969 film Ecce homo Homolka).

Photographs from the aforementioned family archive often capture a world devoid of movement, full of scaffolding, fences, and blockages or, on the contrary, empty places—even those that are now overcrowded with tourists (photo 1). The housing "blocks" (the official name for this type of building) reduce spectatorship to a neutral, necessary minimum (photo 2). In one of the photographs, the spectators are symptomatically looking at themselves, but the event is missing. This photographic metaphor occurred by chance when my father captured an empty stage, the backdrop of which features a large-format photograph of the audience (photo 3).

II. Patina, Destruction, Stains

Traces and stains function not only as relics or evidence but also suggest absence, something missing. It is over this absence that memory and imagination can begin to unfold. Traces point to the body as well as to broader, collective events, and through the medium of the fragment, these elements become intertwined.

Adriena Šimotová incorporated imprints, erosion, and wrinkles into her works, focusing on temporal aspects (that, according to "classical" theories, do not typically belong in visual media). In the stagnant time of the normalisation era, her works inscribed an alternative history with the subjective qualities of emotions, physiological sensations, and feelings. Petr Veselý and Josef Žáček integrated patina, shadows, stains, blurring, and mere fragments or relics into their work—elements that the viewer pieces together and completes in their imagination, linking them with their own memory traces and pathways.

Tomáš Ruller and Marian Palla preserved in their works the relics of alternative rituals, which served as a counterbalance to the official cult-like events and processes of the time (where crowds of spectators and grandstands acted as showcases for official oversight and gaze). A similarly "magical" approach to creation was maintained by Petr Nikl, who often explored childhood as a quasi-idyllic, static state of society—perhaps desirable in that era—necessitated by the totalitarian political order, a period of blocked time.

The undefined ordinariness, stretching into monstrous formlessness, is reflected in the work of Zbyšek Sion, Michael Rittstein, and Otakar Slavík: the chubby shapelessness of a giant child in Slavík's painting, the ghostly gardening and greenhouse vegetable successes in Z. Sion’s works, etc…

The apparent opposite of formlessness and blotchiness is automation, construction, and the mechanisation of time, life, and actions. This reduction and simplification of life into a few basic tasks, alternating with pseudo-extraordinary activities, can be seen in the hypertrophy of organisation in Stanislav Diviš's paintings, which sometimes depict systems like mass gymnastics festivals (so-called Spartakiads) or the era’s reduction of ornamentation. Similar aridity and a completely "postmodern," but rather normalisation-era, trivialisation of “romantic” desires for novelty and mystery can be found in the ironic works of Antonín Střížek.

Within patina and decay, there exists a fascinating survival (“Nachleben”) of older epochs, altered and varied memories, and different versions of memory and history. In our family archive photographs, patina, certain folds of time, and destruction also appear. Memory work unfolds over these elements (much like imagination is spurred into action by a shapeless stain). These photographs also testify to the blockage of time and movement, to the collapse of historicity: various demolitions are captured, as well as the city's confinement in barriers and scaffolding (photos 4 and 5). The photograph with a blotch of the empty, rain-soaked Letná Plain, with a phantom view of Hradčany on the horizon, is for me one of the most striking visualisations of the feeling in which horror vacui intertwines with the urge to imaginatively complete the blotched patina of this era (photo 6). It seems that even in this period of stagnant time, there existed small, alternative histories, based on the work of subjective imagination and memory.

III. Material, Simulation, Substitution

The "normalised" life could overall be perceived as a kind of substitution, pieced together from available, low-quality materials. It recalled hardboard – we essentially lived not only in a concrete world but also a hardboard one (in the GDR, hardboard was even a popular surface for painting). Hardboard has two sides, two interesting textures, smooth and rough, but who knew what happened inside its adhesive entrails… In the normalisation era, real events were substituted with something pre-prepared, instant, and repeated with a sense of jaded sarcasm – even events were replacements (besides, we also had HPL, Masonite, chipboard, amphetamine, Tesil fibres, nylon, etc.).

Non-artistic materials in creative work can in some way comment on the substitutional nature of the time (though that’s not their only meaning – they also speak to changes in artistic approaches, the relativisation of traditional hierarchies, and so on). Vladimír Kokolia used untreated canvases, and viewers can partially interpret them as a reflection of the "unfinished" nature of the time. Marian Palla incorporated "ordinary" materials like clay, twigs, and strings into his works; Věra Janoušková used enamelled sheets from scrapyards; Alena Kučerová allowed the unique effects of metal printing matrices to shine; and Margita Titlová Ylovsky created "action painting" using lipstick. These instances of "substitution" or the different impact of unconventional, non-elite materials in art suggest that artists in this historical context wanted – and had – to fundamentally change their approach to creation. "Poor" materials are somehow closer, more intimately related to humans than, say, Carrara marble, but they also speak more of temporality, transience, and the collapse of hope.

The photographs from our family archive are also marked, scarred by the limited possibilities of ordinary photographic materials of the time – they are riddled with blotches and blurriness, marks, and scratches. In one older photograph (from 1967), we see an advertisement reading "Malcao strengthens" (photo 7); this was a substitute drink, replacing coffee, but also creating its own unique taste culture. This uniqueness represents a general characteristic of the aforementioned substitute materials. Today, they are sought after and have become a certain legend (a half-ironic myth).

IV. Farce, Event, Ritual

A reaction to the blandness of sensory stimuli or the grotesque artificiality of official events, festivities, and quasi-experiences of the time could be an ironic or postmodern reflection, parody, or exaggeration. Caricature and distortion were often used together, as monstrosity, at least in terms of form, closely resembles grotesqueness, with the two representing two sides of the same visual principle. The "experiences" of the time were generally tied to leisure activities – weekend cottages, holidays, gardens – subtle enhancements within the bounds of the law, in the words of Czech writer Jaroslav Hašek. Beyond this, experiences were related to the tame and dull pop culture of the period. We see such pop-cultural reflections and hyperboles, for instance, in Jiří David's painting I Say It with a Song, and a kind of pop-cultural pattern also emerges also in the paintings of Richard Konvička. Pseudo-aesthetic experiences of difference, novelty, and extraordinariness appear in Zbyšek Sion's paintings of fantastical greenhouses and Čestmír Suška's sculptures.

Rituals sui generis are present in the work of Marian Palla, showing a kind of new prehistory as a fitting alternative to the spiritual emptiness of the era. The performative events and their relics by Tomáš Ruller have the same nature of a private ritual act. Petr Nikl plays with the magic and mystery of childhood, extending far beyond the boundaries of adult life. The mystery and openness of the ritual impart the artistic event authenticity (authentic events during this time were considered by deconstructivist philosopher Jacques Derrida).

In one of Bedřich Dlouhý's paintings, there is a peculiar fold in an otherwise nondescript landscape with a pond or sludge lagoon. It’s a narrative fold or rather a plot that, however, never unfolds—a non-event, where time stands rigid and unmoving.

The family archive documented a considerable number of private farcical and parodic events designed to somewhat overturn the paralysis of the era. These photos captured the unusual, the narrative, "islands of positive deviance." The fossilised era was disturbed by the monstrosity of farce, which represented a kind of “line of flight” into imagination, hyperbole, and eccentricity. A circle of family friends staged a "battle of the frogs and mice” with protagonists made of paper and hidden in a Trojan horse, which was dragged through night-time Prague to a friend’s flat, where it was left as a surprise the next morning (photo 8). Other examples included the diagnosis of a tin coffin (photo 9), sent later via rail mail to one of the friends, or a parody of Max Švabinský’s Madonna From Chodov (photo 10), all of which revealed an attempt to disrupt the organised order of the time.

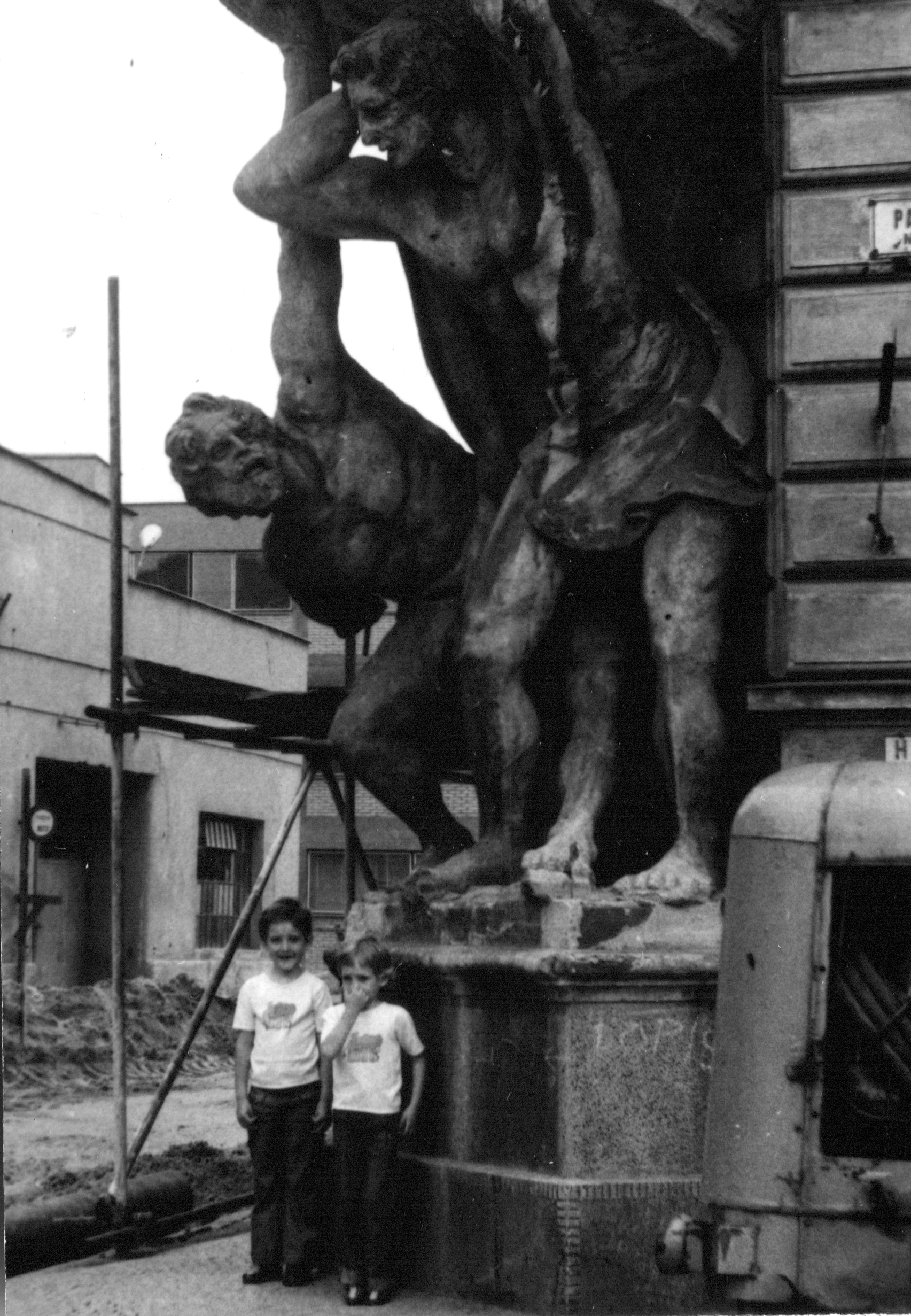

Further attempts to add flair to the aesthetic field can be seen in the archive’s photographs, for example, in relation to the era's interest in origami and ikebana, or from museum visits, monuments, and trips (photos 11 and 12). Such images contrast sharply with the official appearance of then “events” (photo 13). The family archive’s photos contain reflections and parodies of the era's reduced spectrum of events, similar to what we find in contemporary visual art. In such a situation, creating one's own experiences and eventful environment in the form of rituals, farces, and alternative activities appeared to be a suitable strategy for spiritual survival.

It seems, then, that the Eighties were, on the surface, rather invisible—very little seemed to happen in the official sphere, and those events that did occur appeared too contrived to allow any immersive engagement or identification. All the more was happening "beneath the surface," within private events or the sphere of handcrafted lifestyles. The Eighties are thus "in/visible" through these two alternating perspectives.