How did you get into curating? What do you consider to be the turning point of your career?

I have always been attracted to contemporary live art. At the very beginning, it's also the influence of my parents. My father loved art and had collecting inclinations, albeit quite conservative. Although I graduated with a traditional degree in art history in Olomouc, in practice I ended up studying contemporary art. I see curating as a creative job that allows me to work more freely and come into contact with a lot of interesting people. The turning points were always related to specific people I met on my curatorial journey. Thanks to them, I was able to realize major exhibition projects in important institutions (Fundamenty & Sedimenty, GGeometrův zlý sen, Ivan Pinkava: Remains, Motýlí efekt? / The Butterfly Effect?, Jehla v kupce sena, Mezipaměť / Cache etc.), or to publish large-scale book projects (Inverse Romance, SPECTRUM).

For two decades now you have been trying to advocate the medium of painting in the field of Czech art. What is the position of this medium on the art scene today?

Today painting is back on the scene and no one is surprised. I have lived through times when painting was buried as a regressive and unviable medium, and those who painted were subjected to the ridicule of those who constructed the "evolutionary" development of contemporary art in a slightly more accelerated and inappropriate way, as it is, after all, being shown today. The beginnings of my curatorship are linked to the defence of the contemporary image and its right to exist in every successive emerging artistic generation. One of the key projects in this direction for me was the exhibition RESETTING / Other Ways to Materiality, realized thanks to the understanding and helpfulness of Karel Srp at the Prague Municipal Library (GHMP) and in collaboration with Petr Malina at the turn of 2007–2008.

What do you think has influenced painting to be back in the spotlight and how do you think your continuous work may have influenced this?

The return of interest in painting can be seen through two basic perspectives - the local and the global, but these perspectives cannot be separated from each other as they are ultimately conditional. If we begin with the local, then the historical situation of the post-communist bloc of Central and Eastern European countries, which first discarded their traditional artistic practices in favour of new media, only to rediscover the means of expression of their own cultural identity, differently, updated, differently, after the "revolutionary" intoxication of social and political change had worn off, played a role in the return of painting. This development was particularly marked in the former NDR, Poland, Romania and in our country. On a global scale, i.e. in the awareness of the cultural identity of Central and Eastern Europe, all of these countries were ahead of us. Why this is so is a subject for a longer explanation. This situation has been replaced by the stage of post-colonialism, which seemingly does not concern us too much, but if we relate this topic to the hegemony of the former Soviet Union towards the Czechoslovakia, then a large relational field opens up for art, which nobody wants to enter. My curatorial work, at least I hope, has contributed and is contributing to not sacrificing the old for the new. Not to perceive art in a strictly developmental way, and also to maintain the dimension of natural human sensibility and sensitivity that is alienated from us by the various mechanisms and ideologies contained in the models of market, post-media and post-information society. Every emerging generation has the right to paint. And each succeeding generation will do it to some extent differently and similarly... What is apparently at stake here is the constant need to reproduce and share certain experiential principles, for which the most appropriate linguistic system of communication is the image and the painting medium. Some people don't need a painting, others can't imagine art without it. It is similar to poetry.

After eight years, the Vyšehrad Gallery has finished its operation, what was this working phase like for you and which projects were the most memorable for you?

Prague's Galerie Vyšehrad was a unique opportunity to create a long-term independent exhibition dramaturgy. As a curator of this exhibition hall, I realized over fifty exhibitions here in eight years. The exhibition concept focused on contemporary painting as conceived by the generations of artists born in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s. In addition to established artists such as Daniel Pitín, Ladislava Gažiová, Josef Bolf, Veronika Holcová, Daniel Hanzlík, Adam Štech, Lubomír Typlt, Jana Farmanová, Robert Šalanda, Adéla Janská, Marek Meduna or Zbyněk Sedlecký, the exhibition also featured artists who were more of a beginner at the time, such as. Vladimír Véla, Jan Poupě, Dana Sahánková, Jakub Janovský, Adéla Součková, Jakub Sýkora, Monika Žáková, Ester Knapová, as well as start-up authors such as Argišt Alaverdyan, Marta Zechová, Jiří Marek, Radka Bodzewicz, Annemari Vardanyan and Jakub Čuška.

What were the reasons for the gallery's closure and what do you think about the whole situation?

The Vyšehrad Gallery closed purely because of the decision of the new director of the NKP Vyšehrad, whose development concept for Vyšehrad, at least according to his own words, did not fit the gallery. It was also argued that the area of the guard tower above the Vltava river, where the gallery was located, needed to be structurally repaired. I did not receive a satisfactory answer to the question why the gallery could not continue its current operation there. In addition, just before the closure, a Christmas exhibition by Alena Ladová, visibly financed by the gallery, appeared in the gallery, which I regard as an insensitive step or an intentional one, given the previous exhibition concept. What will be the operational content and status of the space after the renovation is up in the air. But maybe everything is completely different and the denouement will be surprising... I don't care anymore.

You also worked as an assistant professor in Jiří Petrbok's drawing studio. What is it like to work with "finished" artists on the one hand and students whose work is still in development on the other?

I worked at the Drawing Studio at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague as an assistant professor from 2011–2018. Then, for personal reasons, I decided to leave the studio. To this day I do not regret these seven years. It is a great experience for me to be there when new artistic personalities are being formed and you can contribute to it, even if episodically. I also managed to see a strong generation of artistic authorities at AVU, which for me are Jiří Sopko, Jindřich Zeithamml, Zdeněk Beran or Jiří Lindovský. I am glad that I had the opportunity to get close to them professionally and, one could say, amicably. I appreciate it very much and I am glad for it.

What names are in your main curatorial "stable"? And do you have any dream artists you'd like to work with in the future? Either from the Czech Republic or from abroad?

Since I am not a gallerist but an independent curator, it is impossible to talk about stables. In my work there is no standing. Everything is in motion. This is both an advantage and a disadvantage of this independent position. For a long time I have been working with a number of artists of different generations. In the past, for example, it was an intensive collaboration with Lubomir Typlt or Jiří Petrbok. I have done many exhibition and book projects with Ivan Pinkava. A few years ago, I brought the Slovak Viennese Silvia Krivošíková to Prague and the Czech Republic for the first time. But I get along very well with many artists across generations and expressive media (not just painting!). If I were to name all the names here, it probably wouldn't even fit :). I'm glad that Michaël Borremans was happy with my text and that thanks to Petr Nedoma I was able to prepare an exhibition featuring Eberhard Havekost and Frank Nitsche, for me essential painters of the Central European space (Mezipaměť / Cache). The challenge for me is to map the painting studio of Jiří Sopko, I would like to focus on the contexts of contemporary Central European painting (Czech Republic, SK, Austria, Poland, Germany, Hungary). Besides the painting "superpower" - Belgium, I admire solitary artists across the global scene. But I also like to go back in time, for example to Nicolas de Staël, the German Expressionists or even to Peter Parléř.

What projects are you preparing for 2023? Possibly even later.

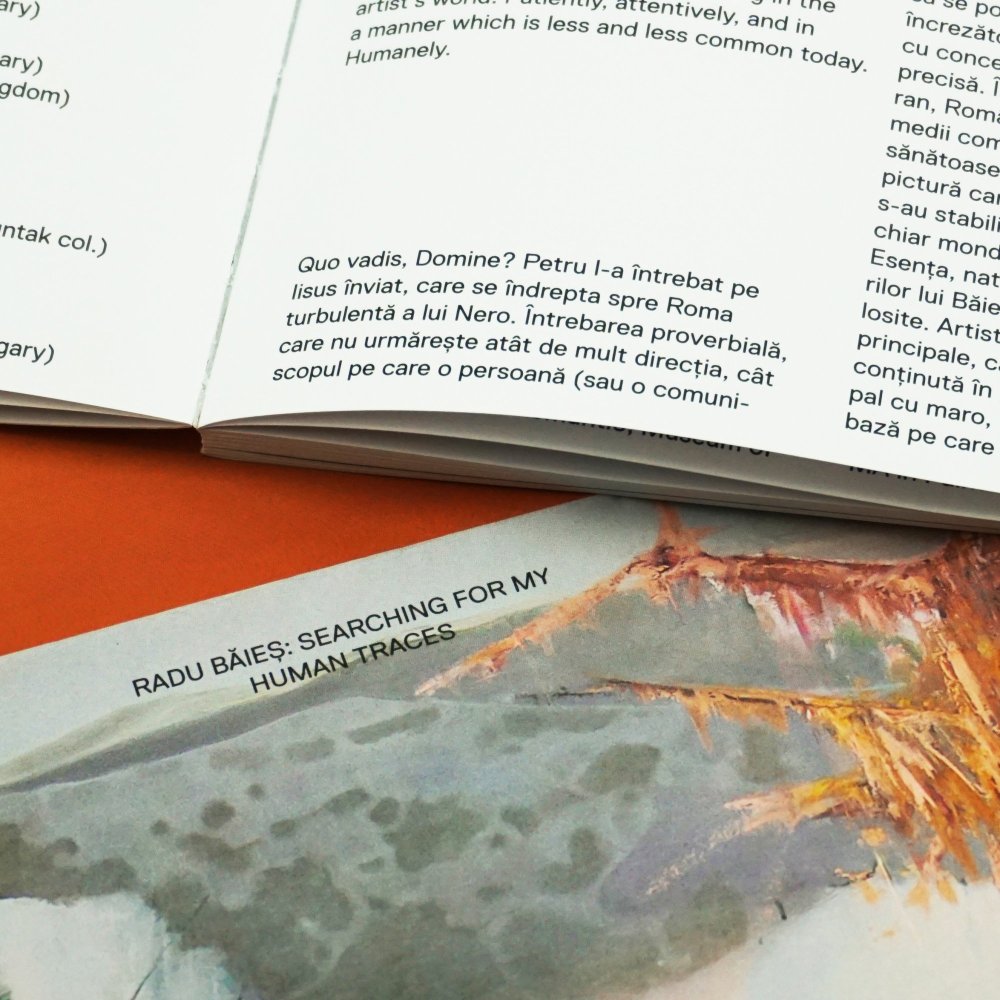

By the way... a monograph by Radu Belcin, a Romanian painter living in Berlin, which I co-authored, will be published now in the spring. The collective exhibition TRIP will start soon. We are arranging an exhibition with Jakub Janovský in Trafo Gallery in Prague, the Prague exhibition of photographer Miroslav Machotka, painter Aleš Brázdil, the Budějovice exhibition of painter Alžběta Josefa. There are also Broumov projects, this year with Petr Veselý and Miloš Šejn, a joint project of Petra Švecová with Radka Bodzewicz, etc.

You studied in Olomouc, where Telegraph Gallery is based. Since then, however, you have been working mainly in the Czech Republic. What drew you to study in this city?

It was partly by chance, but lucky for me. I had failed the entrance exams to the painting studio at the University of Applied Sciences, and I was in danger of having to do the military service that was still compulsory at that time. I submitted three applications for art studies and two of them were successful. I preferred Olomouc to Plzeň and thus prolonged my youth in Moravia at the art history department in the Czech Republic, which was probably the best in terms of personality at that time (Ivo Hlobil, Alena Nádvorníková, Rostislav Švácha, Milan Togner, Marie Mžyková, etc.). It was a demanding study, but I still live from it.

How was it to return after almost a decade of sitting on the exhibition board of Caesar Gallery?

I have curated a number of exhibitions for Galerie Caesar in Olomouc, mainly of young painting. That's probably how the idea of inviting me to join the gallery's exhibition board for a while came about. But even that was actually a long time ago :). Returning to Olomouc is always associated with a special nostalgia and I can't help it, I spent five years of wonderful student life here. And I have good friends here.

You are the curator of the exhibition Zbyněk Sedlecký: Inscenation. You have collaborated with Zbyněk Sedlecky on several projects. For example, at the Topičův Salon, at the House Gallery in Broumov or at the Trafo Gallery in Prague. How did your collaboration start?

We were introduced around 2003 by the painter Petr Malina in the framework of the exhibition projects 6. 5. (NoD Roxy, Prague) and ARTNOW.CZ (Mánes Exhibition Hall, Prague), which we, as enthusiastic youngsters, were putting together on our knees. Since then, Zbyněk has been one of the artists with whom I collaborate as a curator regularly, often and gladly.

What can visitors see in this exhibition?

The exhibition Inscenation is a continuation of last year's project entitled Requisite at Prague's Trafo Gallery and thematizes the transformation of the painting genre in the juxtaposition of several levels of, shall we say, pyramidal authorial reflection and self-reflection. In Olomouc, a wider selection of paintings from the last two years can be seen. Self-portraiture is often found here, and three basic subject areas intertwine - the costume of a uniform, a mask with a white beard and a restored object of a Baroque angel. Human hands are everywhere present as an instrument of first, immediate touch and recognition. All the figures seem to float in a kind of temporal formaldehyde. The exhibition contains a strong generational message about the transformations of self-perception and the changing relationship to time and space within historical and personal constellations. The tension between life as constant change and its figurative suspension in an otherworldly and mystifying staging is what deepens the expression of the painting itself and what needs no clear-cut interpretation. All you have to do is tune in and look hard. Visitors can also look forward to the artist's first major monograph, which will be christened during the exhibition at the Telegraph. Pavel Tichoň has contributed to its graphic design.