The interview was conducted on the occasion of the group exhibition Brave World at the Telegraph Gallery. The exhibition is curated by Tevž Logar and conceptualized by Gregor Podnar. Interviews with the artists were conducted by art historian Barbora Kundračíková, who works at the Department of Art History at Palacký University and the Olomouc Museum of Art-SEFO.

The New Yorker described you as “a wildly imaginative thirty-one-year-old Brazilian artist who is fascinated by the macabre”. Apart from your age, do you agree? Is your imagination wild and macabre?

Hello! Uhhh I really don’t know, it depends on the point of view. I do like spooky sci-fi movies and some kind of “dark” and sexy Japanese animations, but I also like goofy cartoons and bright colours that you can find in the sports industry, a supposed “healthy activity”. I usually say that my work could be seen by children and adults without any censorship. They can see different moods, like playful and fantasy or sexuality and violence because it depends on their backgrounds and what they have been exposed to. I mean, many of my works are related to my own experiences, including traumas and moments of joy because they are based on life, and I believe it can be wild and macabre sometimes. A way that I found to deal with this hurricane of feelings was talking about it through psychoanalysis or art. In psychoanalysis sessions, you don’t have a goal to achieve, you just go very intuitive, digging and finding treasures or sometimes trash, but even trash is important to the process. I believe my creative process is like this.

What does this element of the macabre mean to you? Do you approach it directly? Do you play with it? Do you use it as a tool, and if so, what purpose does it serve?

You see, I don’t really see these elements as macabre; I just do them very intuitively. They may end up with a macabre aesthetic, but it’s not a conscious desire. I feel sometimes it’s like you telling someone a story that happened to you, like stepping in a dog’s shit with your new shoes: everybody starts to laugh but it was not a joke, back then you were very mad about it. The case is that we socially learned that it is funny to step in a dog’s shit. I think it's funny, too. The feelings like disgust, repulsion, or thinking something is macabre are the same: we’re programmed by society through movies, advertising, family, etc. what is socially acceptable and what is repugnant. I believe the line that divides good and bad is quite fine. There is this saying: “The road to hell is paved with good intentions”.

One thing that seems important to me here is your willingness or desire to fascinate and seduce. I imagine you as a spider sitting in the middle of its web, waiting for someone innocent or brave enough to touch it – and then! You grab her or him from behind. Am I right?

That’s funny! What usually happens is that I am the innocent person whom the work catches in the web! It’s crazy because as I said, my process is very intuitive and many times the works end up looking like something pervert. Like a very innocent finger that ends up looking like a penis. So, I’m with them in this web.

There's still that doubt involving the concept of beauty, but to be honest, I find your work literally beautiful. You may know Helen Oyeyemi; her latest novel, Gingerbread, somehow reminds me of the same physical experience. A spicy taste fills the mouth – it is delightful and warm, but suffocating at the same time.

I just love the warm metaphor! Thanks for this! I usually laugh because many people tell me that I deal with bad taste but I’m not, because what I put in my works are things that I considered good taste. They include my old outfits sometimes, like shoes. So basically, people are saying that I have bad taste. I believe this concept of polarized stuff is old-fashioned, people just want to be happy without judgement. A taste is not good or bad, it is just a taste.

Does storytelling in principle help you with that? I mean – establishing some sort of hidden narrative encompassing the concept of beauty as an internally diverse term to anchor the work.

Yes! I came from a cartoon and comic background. At the beginning, I was at the university to work with comics and studio animation. Working at Studio Ghibli was my desire. I was so sure about my choice that I studied Japanese for seven years instant of English. So, I grow my creative process through narratives. Even when I made abstract works with basic colours such as red, blue, yellow, and white, it was about the narratives that the colours could find through advertisements. Red and white became the Marlboro box, for example. So, all the works have their own narrative, even if in the end it doesn’t really matter.

I suppose that the story you are telling is in some sense global, playing with anthropological similarities rather than differences. Am I right?

Most of my works are based on feelings and emotions through materiality. Feelings are universal, but the ways we experience them are different. For example, the fear that a woman feels when she is walking in an alley at night is different from a man. Men usually are afraid to get robbed, while women are afraid to get raped. The way we experience fear or happiness, or any other emotions depends on who we are. So, I like to present a situation through a narrative and materials and let people feel it freely. It could happen that they don’t feel anything at all and that’s okay too. It’s also a feeling.

And if you could describe in words the work presented in Olomouc, how would you do it? How would you build the story?

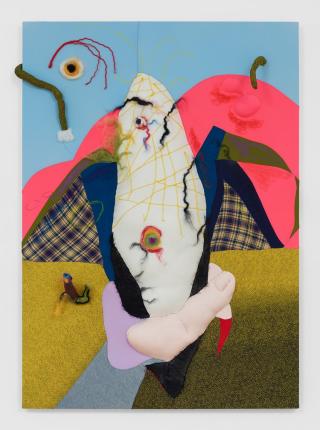

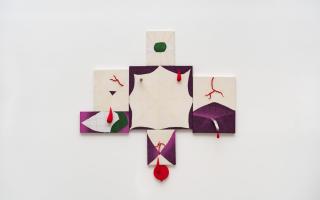

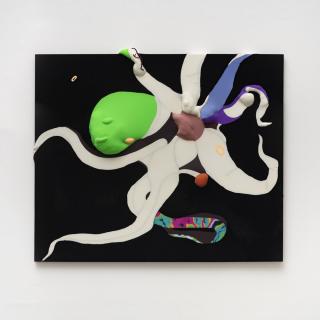

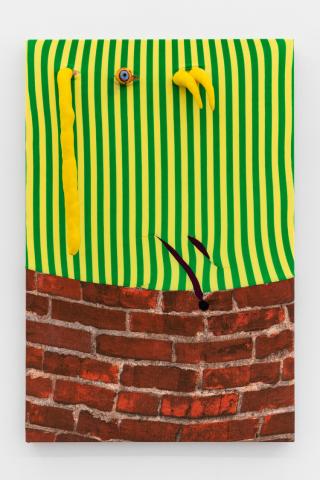

Skull praying is based on my religion. I’m from Umbanda and we believe in spirits that guide us during our life. Exu Caveira – Exu Skull – is one of the spirits that help, protect, and guide me. Telepathic cuddle is based on the memory of my husband cuddling me, sleeping very peacefully, while I was freaking out with insomnia. Inimigos do fim means something like Party until the end of times! I have just started to wear high heels shoes and it’s very powerful, but my feet hurt a lot during parties. I made Corn TV in the hotel room in Vienna and finished at Telegraph. I love to work during my trip at the hotels because I feel like I’m camping. So, it’s made with toilet paper, glue, and many other things that I found walking in the city. I don’t know why but I’m obsessed with electronic products, so I did a TV.

Yuli Yamagata (*1989) studied at the University of Sao Paulo, where she was born and now lives and works. Her main field of study was sculpture. Since her studies, she has exhibited both nationally and internationally. Yamagata often combines different techniques: painting, drawing, sculpture, and "wall work", as she defines her work with textile materials.

Her work is on the border of surrealism, moving into fantasy landscapes in the mind of the artist herself. Yamagata embraces the idea of the human body, not resisting mysticism and the influences of her origins. The body, it seems, is a strong motif for the artist - in her paintings, it lives a life of its own and refers to its human roots within the framework of "surreality". Yuli Yamagata's work is distinctive for its colourfulness, which evokes a mixture of feelings and can be associated with references to Fauvism and Expressionism. Thanks to the wide range of colours, her drawings have an almost cartoon-like aesthetic.

Autor of the interview: Barbora Kundračíková

Author of the text about the artist: Barbora Křížová

Photo portrait:: Vendula Burgrová

Photo of the installation: Matěj Doležel