The interview was conducted on the occasion of the group exhibition Brave World at the Telegraph Gallery. The exhibition is curated by Tevž Logar and conceptualized by Gregor Podnar. Interviews with the artists were conducted by art historian Barbora Kundračíková, who works at the Department of Art History at Palacký University and the Olomouc Museum of Art-SEFO.

One of your main themes is, if I may say so, connecting and unravelling the relationships between the real and possible worlds. Do I understand that correctly?

I feel that interpretive dichotomies can be helpful for emphasizing a particular feature and for framing a specific field, but they can also easily lead to misunderstanding or schematization. Rather than a straightforward answer, then, I would like to pose a few complementary questions – for example, what does the real world mean, or what is the difference between reality and its potentiality? When does the world-making through our imagination become real?

The notion of the possible, or possible worlds – which was developed in a very stimulating way by Lubomír Doležel, especially in the Czech and European environment – is based on modal logic and in the space of art is linked to the topic of fiction. Fictional worlds are specific examples of possible worlds. Within the traditional theory of art as mimesis, artistic representations imitate or mimic the world, while in the discourse of possible worlds, artistic creations are sovereign entities connected to reality to a variable degree. I perceive this shift in thought as very important because it reveals the transformative power of aesthetics for the audience. In art and artistic fiction, we creatively explore versions of the possible to find or present alternatives to the real. This does not mean that art provides a prescription for how to live, but that it shows us how we can imagine and envisage variations in our lives. And I see this transformative moment as crucial: the experience of the artwork is interwoven into the experience of the viewer, in a way rewriting it and expanding the range of what can be understood as possible.

The above concept can be considered valid for any work of art. I personally like to deal with utopian or dystopian ideas about society and its organization, especially through a gender or power perspective. For example, in my film Releasing Spell (2020) – loosely inspired by Marge Piercy's book Woman on the Edge of Time – I explore the representations of traditional family relationships imprinted on historical sculptures and the possibilities of their transformation or release.

There is a real poetics in your work in this sense – as if only aesthetics, sensual, formal, can function as a kind of connection, or rather as if aesthetics is a rational, even logical way of ordering an internally diverse world.

I think that part of the aesthetic is always both sensual experience and a distinct way of organizing that experience, a set of rules that govern the work of art, norms that have their own logic and language. What I find interesting about contemporary art is the fact that artists are free to choose the aesthetic code and language they want to speak and through which they construct their medium and message. It can be a borrowed language, different from the artistic language, or from media-specific genres. In my practice, I typically work with the crossing and overlapping of media – from sculpture to film, from film to image, and from the image back to sculpture. Traditional sculptural representations appropriated from reality appear in my digital paintings, for example, the installation That’s not a Fairy, That’s a Mum (2021) in the public space of the Vltavská gallery or in films like Releasing Spell, (2020), or Infamia (2022). I also transform drawings into sculptural form, for example in the object The Family (2021), or create heroes out of them, like in the film Scribbles (2023). In this transmedia approach, I see possibilities for expanding the genre or conveying context in a different perceptual mode – for example, when a spatial experience becomes a temporal experience and so on.

In your dissertation, defended at the Faculty of Arts of Charles University, you tried to prove that "living metaphor functions in works of (not only) contemporary art as their aesthetic model", thus arguing for the validity of the aesthetic conception of art. What exactly do you mean by living metaphor?

This term was introduced by Paul Ricoeur, a hermeneutic philosopher, who defines it as a poetic metaphor of an ontological character, understanding it as a semantic structure with properties like a miniature work of art. He means that living metaphors create a world of “as” with heuristic and re-figurative potential. They are innovative, discovering or synthesizing new experiences within our imagination. The dead metaphors, which stand at the other end of the axis of "liveness", do not bring any surprises and function as traces of the cognitive network of culture and knowledge acquired through the creation of analogies. In the case of a living metaphor, the meaning is indeterminate and anomalous and the recipients actively participate in its co-creation.

For Ricoeur, processuality and mutual understanding are crucial. The understanding of the work is based on the dialogue between the content of the work and the pre-existing knowledge with which the audience approaches it. Its meaning emerges as it contacts the minds of the recipients, allowing them to experience, understand and reflect on the message embedded in the work. This process necessarily takes place in the imaginative act, at the intersection of rational and emotional structures. Reality and fiction then find a platform for conversation, opening and constructing new possibilities.

In my thesis, I extended this concept – originally applied to the field of literature – to art in general and established it as a model of aesthetic experience, using the theoretical concepts of Martin Seel and Alva Noë in particular. The classical aesthetic categories of beauty, mimesis, or representation are thereby transformed into a model of art that can absorb a wide register of contemporary artistic strategies without losing the imaginative and aesthetic meaning of these works in the process of understanding art. The metaphorical character of art in this manner exhibits cognitive features: aesthetic perception is always linked to reflection and the production of new experiences. Art is not confined to an isolated sphere of aesthetic perception without a wider impact in an otherwise rational or pragmatic society. It can therefore be argued that art or artistic principles (not only found in the realm of artworks) creatively reorganize and represent systems and structures in our lives. Through this reorganisation, knowledge, self-knowledge, and emotional participation in a previously unapproachable world can be gained.

And what role does the living metaphor play in your work?

I hope that for the viewers, my works function as living metaphors for our world, that they offer ways to imagine or partake in the experience of someone else or of another place, and that in the end, they lead to an active imaginative and reflective process. The aesthetic experience of my works, however, is best interpreted by the audience itself. While artists may come up with their own explanations, these do not always correspond to how the work itself is experienced.

If you could describe the work included in the exhibition and explain its meaning, how would you do it?

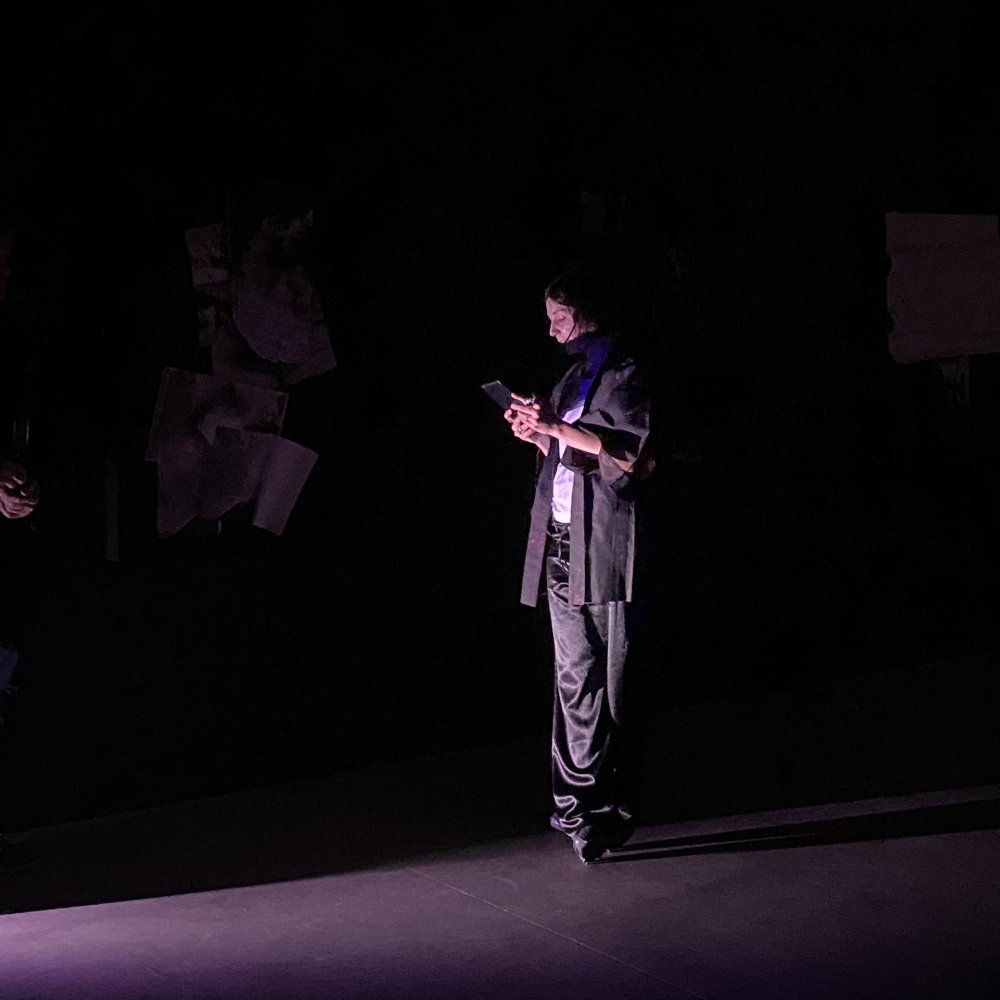

In the exhibition, I am presenting the short film Infamia, for which I have created a sculptural installation inspired by the visuality of archaeological findings. Under the amphitheatre, visitors can see pseudo-fictional objects starkly lit in red belonging to the protagonists of the film – the prostitute Mola and the gladiator Rusticus. These two lovers, who in Roman society fell into the category of persons without a “good reputation”, the so-called infamia, experience in Pompeii the misery resulting from their low social status and their designated role. The instant destruction of Pompeii preserved not only the physical form of the city but also the symbols of its social order. The voice-over in the film is inspired by the found inscriptions in the historical brothel. The vast majority of the sentences scratched into the plaster in the inhospitable squalor powerfully mark male territory, boastfully assessing the performances and preferences of the clients. The one sentence that stands out, full of empathy and care, becomes the film's central phrase: “Mola is dying, the boy Rusticus writes. Who will mourn for Mola?” The chorus at the end of the film, amidst the mythological setting, combines the voices of those who treat all human life with respect.

Markéta Magidová (*1984) graduated from Tomas Bata University in Zlín (advertising photography), Academy of Arts Architecture and Design in Prague (theory and history of design and new media) and Brno University of Technology (video atelier of Jasper James Alvaer, Martin Zet and Jiří Ptáček). In collaboration with the PositiF publishing house, she has released three author books: Typos and Stumbles (2015), Translation (2013) and Home Dictionary (2013).

The summarizing term visual art is the most suitable for defining Markéta Magidová's work. She does not limit herself to one artistic expression and speaks in all art forms with her visual language, which is always accompanied by a strong conceptual focus. The body-individual, social schemas, text as medium, family and crisis. These could be the most fundamental themes characterizing Markéta Magidová's work. Her works' intimate and human aspect is accompanied by a calling for solutions to crucial global issues.

Portrétní foto: Archive of the author

Foto instalace: Matěj Doležel