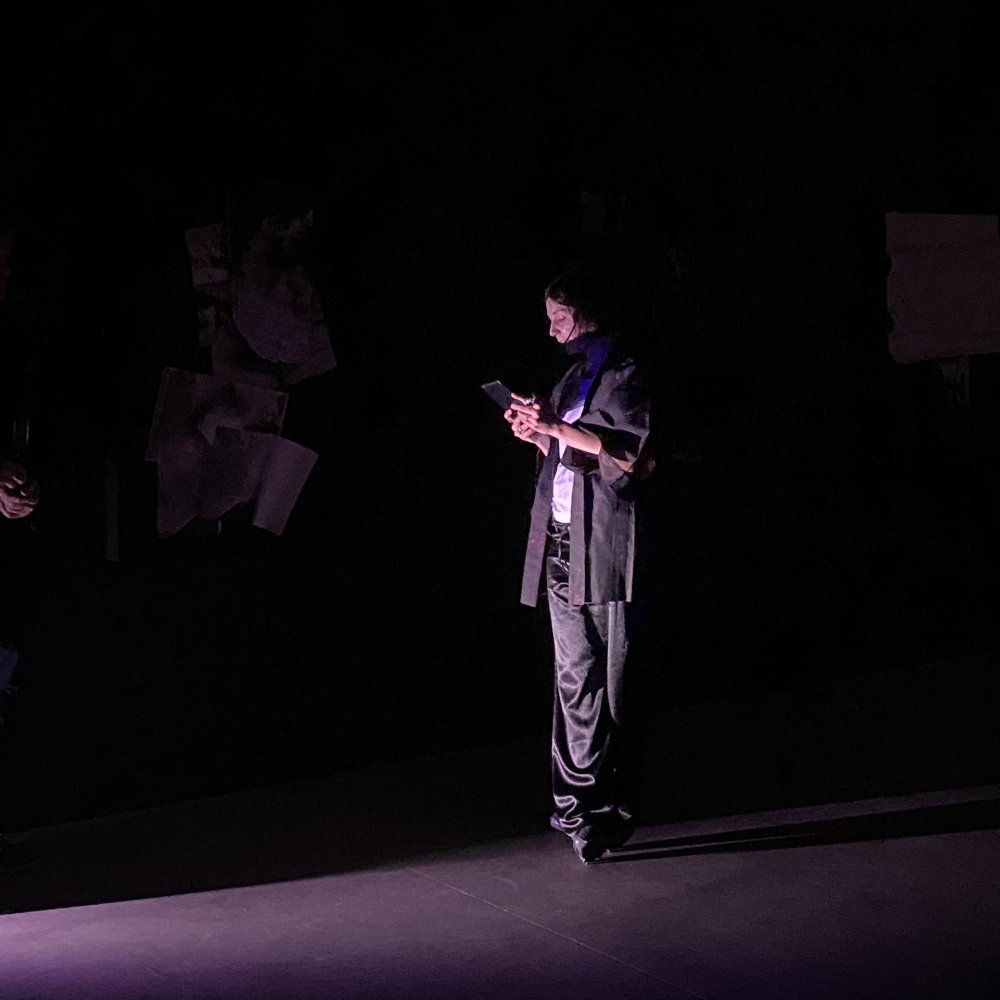

The exhibition Game Owner stages a curious confrontation. At first glance, its title may seem like a playful paraphrase of Game Over, a familiar phrase etched into the consciousness of generations raised on digital interfaces and rule-bound systems of winning and losing. That phrase—Game Over—signals the end of possibility, the failure of agency, often despite the best efforts of the player. It evokes a kind of futility that is both personal and systemic, reminding us of the invisible architecture that governs not only video games but also many of the structures of modern life or in these present days the end of global macro structures, not unlike the fall of the Iron Curtain. Reframed as Game Owner, the phrase takes on a layered significance in the context of this two-person exhibition by Danish artist Søren Dahlgaard and Czech artist Jakub Janovský. Here, the artists are not mere players within a set of pre-existing rules—they are, in a sense, the authors of the game itself. They define the parameters, set the tone, and shape the world into which the audience is invited. The implication is subtle but profound: in Game Owner, the artists are both constructing and subverting systems of engagement, creating works that blur the lines between participation and performance, humor and horror, autonomy and absurdity. The “players”, ostensibly, are the visitors who navigate this visually and conceptually disorienting terrain—a dreamscape assembled from fragments of distorted childhood memories, surreal interventions, and gestures of absurdity. Yet beneath the surface of this playful setup, a deeper, more conflicted dynamic is at work. The true tension arises not merely between visitors and artworks, but between the two artistic vocabularies themselves: Janovský’s “unheimlich”, depersonalized figures of childhood alienation and Dahlgaard’s cartoonish, inflatable sculptures and dough-portraits that invite touch and collaboration. Janovský’s children—anonymized, estranged, and strangely robotic—inhabit psychological spaces marked by absence and repetition. They exist within choreographed rituals, caught in a world of imitative gestures that echo the rigid, bureaucratic order of late communist Czechoslovakia. These figures are not simply portraits of children, but archetypes— symbols of how ideology inscribes itself onto the most intimate layers of identity. Their isolation reflects a world in which agency is illusory, where the mechanisms of control are internalized, and where play has been reduced to performance without freedom. Dahlgaard’s approach, by contrast, embraces the liberatory potential of play. His art is intentionally unstable, full of comedic aesthetics and interactive possibilities. His use of inflatable sculptures resembling migrating tropical islands looking for a new home in times of global warming—and slapstick materials like dough invites tactile, embodied participation. Here, play is not something to be observed but enacted. Viewers become co-creators, explorers, improvising within a loosely defined structure. In this sense, Dahlgaard’s art resists the traditional static objecthood of modern art history; instead, it becomes a living process—transitory, participatory, and deeply human. And yet, these two worlds—Janovský’s enclosed psychological stage and Dahlgaard’s open-ended, performative field—are not opposites so much as they are two sides of the same coin. Both artists reveal, in distinct ways, the hidden structures of behavior and meaningmaking. Where Janovský renders the trauma of systemic conformity, Dahlgaard suggests ways to unlearn it. This is by no means an exhibition targeting children—on the contrary it is aimed at grownups, and play is but a conventional setting or a common ground that allows for the deeper associations to unfold. In Game Owner, we are invited to consider what it means to own a game—not just in terms of authorship, but in terms of collaboration, resistance, and reinvention. The game, after all, is not just theirs. It is ours, too. As spectators, we are confronted with the rules, the roles, and the rewards of playing along. But we are also asked to question the systems we inherit, the performances we enact, and the absurdities we accept as given. In this exhibition, play is not an escape from reality—it is a mode of critique, but also of reflection, experiencing and learning simply through having fun and exploring in ways that are rarely allowed in conventional art spaces.

Christian Kortegaard Madsen, Curator and director of Museum Jorn, Denmark