It is always interesting to look at the art that emerges from a specific place around a time of tumultuous change. Even if artists are not engaging directly with socially motivated themes, it is often apparent through atmosphere as well as subject matter, that something has shifted. Sometimes artists are amongst the first to sense that change is afoot before it occurs, at other times they are amongst the first to react to a societal or political shift.

If we turn our attention to Britain, we can see a particularly clear correlation between the mood of the country and the paintings that were being produced at any given point from 1950. The London School reflected a pensive, introspective mood, whereas the 1960s and 1970s were predominantly given over to the influence of pop culture and a continuing obsession with different forms of abstraction. By the 1980s, figurative painting had been declared dead several times over, and yet like a perpetual Lazarus, it kept being resurrected via different saviours and clever methods of artistic defibrillation. The main argument for its proposed demise was that it was a retrograde medium, surplus to requirements thanks to photography and video art. Much philosophising was made around the subject, and words such as craft and technique were deemed dirty and unutterable. Instead, if painting was to be permitted into important exhibitions and institutions, it had to have an apologetic – irony being the most favoured recourse. And so, the era of the YBA’s (Young British Artists), was born and kept its stronghold well into the 1990s.

By the 2000s painting was beginning to be interesting again. There are several reasons why this shift occurred. One theory being that the digital camera and much later, the rise of social media and the ever-intrusive smartphone called the pre-eminence of photography into question. Painting was suddenly relevant again as – thanks to the internet and programmes such as Photoshop – artists had access to a wealth of images to draw from which they could collage digitally and then translate into the tangible and wonderfully plastic medium of paint, thus reimagining this ancient art form as something cool and current.

Fast forward to the latter part of the first decade of the 21st Century and factors such as sovereignty, immigration, the economy, and anti-establishment politics led to the seismic event known as ‘Brexit’. The effects of Britain leaving the EU, have only recently started to be felt in Britain now that the new regulations have come into force. Add in the impact of covid and suddenly British artists have had to adjust to two significant crises. Alongside this, there has been a powerful movement in Britain to address the gender pay gap and imbalance within the professions and throughout British industry. Additionally, new legislation has been drafted to allow gender politics to become more central to mainstream politics with a focus on creating a more inclusive and tolerant attitude within society.

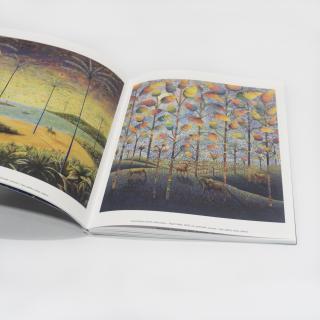

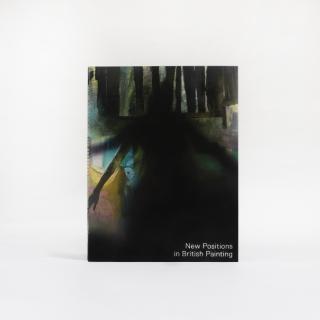

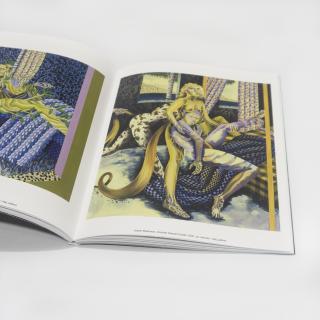

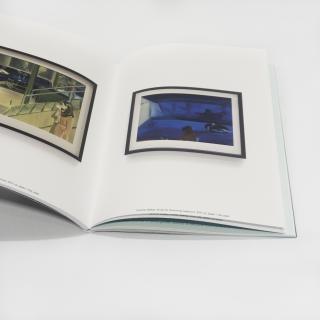

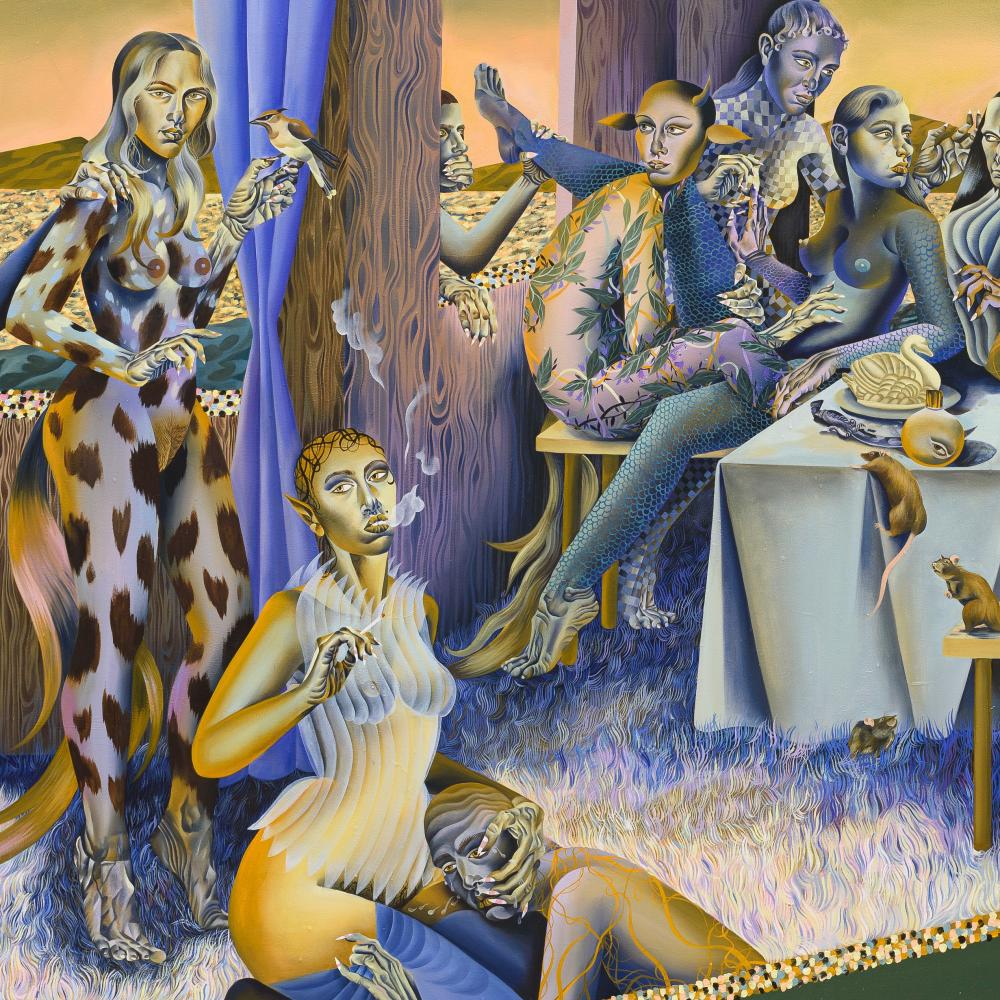

It, therefore, feels both pertinent and timely to curate an exhibition of different positions in British figurative painting, not within Britain, but rather outside of the island, in the midst of a landlocked country in the heart of Central Europe. The artists for the show have been selected for their own particular talent but also because each occupies a unique position today within British painting and offers a truly individual perspective for the Czech audience. Tom Anholt, Jessie Makinson, Justin Mortimer, David Brian Smith, and Caroline Walker are among Britain’s most talented, influential, and interesting painters working today.

Curated by Jane Neal

Supporting programme:

14 9 / 18:00 Presentation: Petr Vaňous

18 10 / 18:00 TEFF23: Guided tour of the exhibition with Jan Kudrna

23 11 / 18:00 Dernissage / Guided tour New Positions in British Painting