This interview was written on the occasion of the upcoming exhibition at the Telegraph Loft, which will be open from 26 to 30 November 2025 as part of this year's Design Days Olomouc. The exhibition will present a dialogue between two distinctive artistic approaches - Czech glass artist Michaela Spružinová and Slovak interdisciplinary artist Jan Durina.

How do you draw the boundary of intimacy within your work - what still belongs in the painting and what remains "behind the curtain"?

I don't censor or proofread the information I share about myself even if it is sometimes stories that may involve a partner. For me, it's always been important to live in truth and give the viewer an authentic account of myself. Visual art gives me a space to narrate that is not so literal, so that the line between private and public is actually almost invisible.

You say that queer issues are virtually non-existent in glass and that there is virtually zero queer community in the Usti, where you live. As a cis straight woman, what appeals to you the most about that?

I've always sought an environment that was on the fringes of mainstream society. My mother had a partner in Rotterdam, and then I dated a bisexual Dutchman myself. I experienced a time when Pim Fortuyn was still in politics and the environment of this community we were going to started to become normalised. I took in that "west wind" which was inspiring for me as an artist and I think that period fundamentally shaped me.

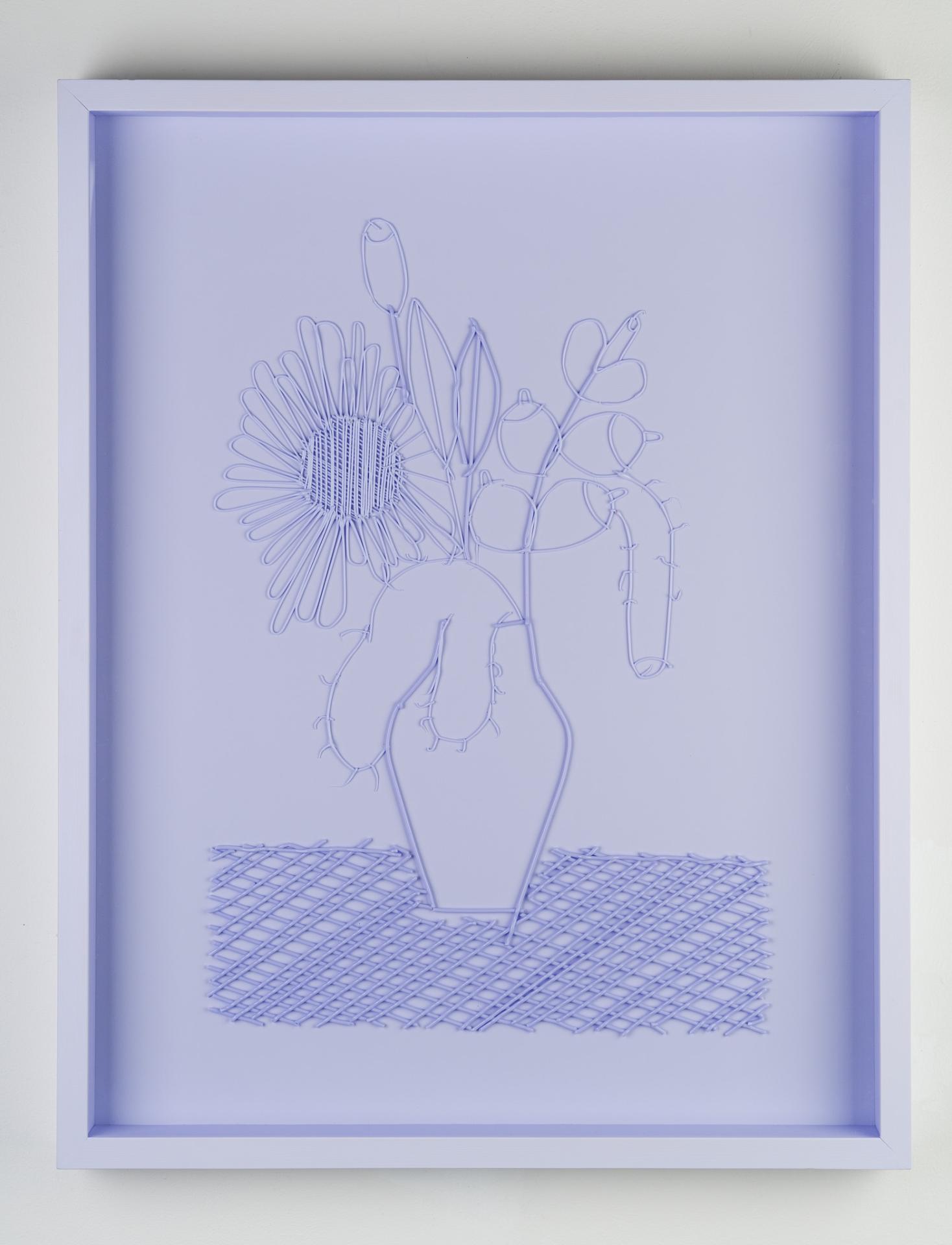

You created a technique called beading, can you describe this technique better? What led you to do that?

I always went against the dictates of the glass community. I was looking for ways to provoke them and push that material boundary a little bit into the impossibly possible. And those beads are a pretty "low" material for a glass artist. Technically, glass is, but it still has a decorativeness to it that is unfortunately influenced by its use, which is fashion. Since I spend 11 hours on the train every week, I've come up with a technique that I can do there as well. And that's just weaving that glass canvas, which I then draw and paint on with other materials.

What do you find works well in layering "glass art" like threads - from floral motifs to the figure?

I never had a studio or facilities for my work, but I wanted to create. So I was looking for a solution that was low cost and space saving. I bought a glass lamp stick torch and began to use tweezers to pull out the components that made up my drawing. At first I composed them flat, but later I wanted to elevate the technique to a craft that would stand up in an international context. So I was folding the components into moulds and just using high temperature to join them together. That's why I won the Ireland Glass Biennale in Dublin, because I did the impossible - hollow objects without using glue.

For the exhibition at Spot Gallery in Prague you created your first blown objects. Was there anything surprising to you when you created them? And how did you enjoy your "first time"?

It was a completely different experience because another factor that influences your work is the glassmaker. He or she has the skill and experience that will translate, willy-nilly, into the outcome of the blowing. And you're also limited by size. I knew that the space at Spot Gallery was generous and needed larger objects than I was used to. So for the first time I used metal drawings to "bring" the glass into the space. I had wanted to make this material connection for a long time, but no curator had pushed me to step out of my comfort zone. It wasn't until Mira Macík did that, who motivated me to no longer just tie myself to galleries that show glass, because he believes that I create free art. And that's what I've always wanted. To break out of that closed circle and be independent of it.

How do you work with a flaw (a bubble, a hairline crack) - when is it a flaw and when is it proof of the life of the material?

I have been recycling glass waste since I started my work. So I consciously work with poor quality glass. I take responsibility for what my work is made of and how energy intensive the actual production of the glass is. That's why I also have pretty simple, reduced workflows to make that production as energy-intensive as possible. Paradoxically, it's a much freer approach to glass because it has the highest demands in the context of craftsmanship. At the same time, I take the risk that glass with defects can cause stress and breakage in the kiln. When a fused sculpture has bubbles on the surface I work with it as a revival of a dead surface. When the glass creates a different surface coloration by misadjusting the fusing curve, I repeat the mistake and use it in the concept of the whole work. It's like de-greasing a surface that looks like stretch marks on human skin. All these aspects support each other and help me create a truer image of myself.

When do you know a piece is finished? Do you have your last touch test?

It's quite a long process because part of the piece is the adjustment, which is an essential thing with glass. Because I have fragile pieces I also have to work with the fact that glass will be handled by people who have no experience with it. Of course, you can work with what you already know and it works for you. So you go for safety and the process is simple from design to implementation. But I've been incorporating other materials into glass a lot in the last year and with those you need a time horizon to prove their stability. At the same time, I turn to my friends who do a little proofreading of my kitsch, which is always prevalent in my work. I finished the last painting I had almost finished after watching it for two weeks. It was only after constant watching and thinking that I was able to create the last detail, which is actually the main motif of the composition.

You have traveled a lot. What did Berlin, Ireland, Israel, Holland give you and what did you consciously bring to Zlín, where you teach in the Glass Studio at Tomáš Bat'a University?

You have been able to work with glass in the context of a conceptual approach. At the time I was studying, I first encountered such thinking in glass in Israel. It was not yet common in our country, the material stereotypes were still repeated. So I try to run the studio in such a way that everyone builds their own authorial path and likes the work. They didn't dumbly do assignments, but sought them out, and that's because after graduation they go into the art market on their own.

How do you set up a safe environment for students in the studio? And how do you work with students' freedom of creation?

I always try to maintain respect for my students. We are equal partners and we enrich each other's experience. I'm not able to cover all the art techniques myself, so when we have someone in the collective who works with cyanotype on glass, for example, I like to learn from them. I appreciate that they have chosen me to guide their studio and I want to provide them with the utmost expertise. We do not tolerate bullying, homophobia or other forms of aggression towards others. If I feel there is a problem in the collective, we communicate it right away.

What are your students teaching you now?

I know that the younger generation is resonating with many educators at the moment, setting very different views of their identity. I am sympathetic to them because I am partly Hungarian and have been exposed to a different world all my life. The part of Eastern Europe where I go has a completely closed view of this issue. And even I have always been a strange, incomprehensible element for them - an artist. Which actually keeps me in this healthy tension to promote openness and spontaneity and to support democratic principles. In the context of the current political situation in Slovakia and Hungary, I already see this as part of my identity. They are a great inspiration for me, if only because they open up new perspectives and experiences for me to draw from.

What was the last move that really scared you - and yet you went for it?

It's a project I've been working on for two years. It involves work camps for a Czechoslovakian glass company where they were grinding components. Many people had work-related injuries that caused amputation of limbs. At the same time, many people took their own lives because the working standard was impossible to meet. For example, dissident Jiří Gruntorád was in such a camp. I meet with political prisoners who went through these camps, visit archives, and together with a historian and curator, we put together an exhibition project that puts that polished glass tinsel into a different perspective.

What works have you chosen for your joint exhibition with Jan Durina at the Loft?

I am preparing new works for this joint exhibition. But to introduce my work to an audience that doesn't know me, I included glass monochromes in the selection. This is because the whole space is painted black and I want to prepare works that respond to its specificity.

Michaela Spružinová is a glass artist who boldly defines herself against conventional glass work in the Czech environment. She works with the human body in its natural state, challenging society's stereotypes of beauty and exposing the fetishes of the consumer world with an authentic dose of sarcasm. Her unique approach manifests itself in the challenging process of upcycling waste glass, from which she creates objects that reveal the paradoxes of consumer culture. She graduated from the Glass Studio and the Studio of Curatorial Studies at the Jan Evangelista Purkyně University in Ústí nad Labem. She has completed internships in Hungary, Israel and Turkey. She has exhibited all over the world, for example in Germany, Ireland, Italy, the United States, Sweden and Denmark. She is a lecturer at the Glass Studio at Tomas Bata University in Zlín.