This interview was written on the occasion of the upcoming exhibition at the Telegraph Loft, which will be open from 26 to 30 November 2025 as part of this year's Design Days Olomouc. The exhibition will present a dialogue between two distinctive artistic approaches - Czech glass artist Michaela Spružinová and Slovak interdisciplinary artist Jan Durina.

In your early work you expressed yourself mainly through photography. Where did you develop an interest in this medium?

Na high school, with the advent of the first social networks. I was studying fashion design, and I photographed my then-classmates' creations. Eventually, I had a camera with me practically all the time - it was my tool for instantly capturing visually how I was feeling. With just a few clicks, I was able to share these images online with a community of people from all over the world who were as passionate about photography as I was. It sounds corny today, but in the early days of social networking, it seemed like a miracle to me as a kid from a small town in Slovakia.

In your photographic series Mountain, you capture your self-portraits while wandering in the High Tatras, and you wanted to rediscover the place where you come from. I personally feel a great disconnect from where I grew up, did you have a similar experience? Or have you always felt a certain connection?

I love Slovak nature. I think it is one of the most beautiful in the world. It is the main reason why I will never disconnect from Slovakia.

In the series, then, you mix gentle masculinity with a parody of toxic masculinity. During your travels, have you figured out what kind of man you would be if you hadn't left Slovakia?

Quite frankly - I don't know if I would even be here today. I knew from a young age that Slovakia was too small for me. I was suffocating there. I felt the need to lose myself in the crowd while not losing myself. I couldn't do that in Slovakia. But I never wanted to move away too much because it is important for me to stay close to my family, friends, nature and to stay in touch with Slovak culture, which I care a lot about.

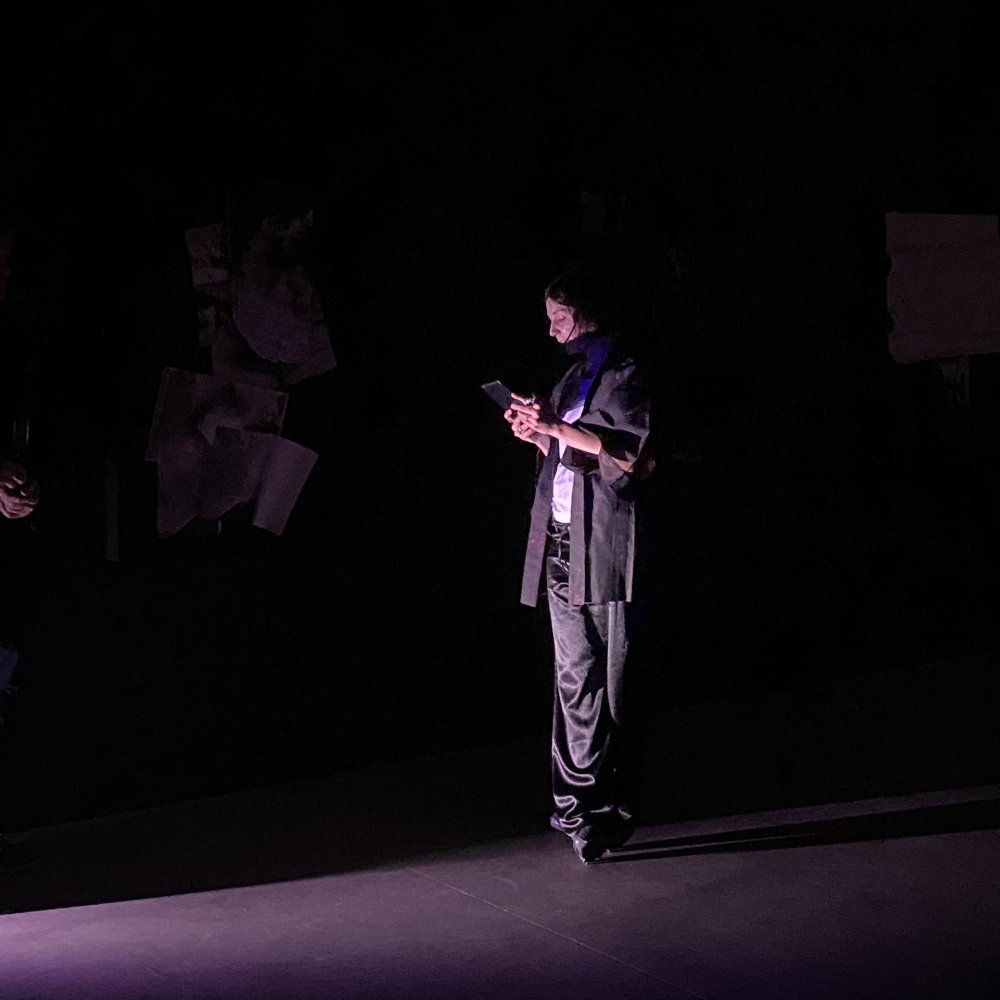

During your life in Berlin, you were around club kids, which you later left. Was it this time in your life that led you to performance art? Do you remember the moment when you realized that this was going to be your next means of expression?

Yes, definitely. I remember the moment when I got into the environment of Berlin's underground queer club events. I watched in amazement the performances of avant-garde musicians/musicians, performers/performers and felt how much I too longed to stand on stage and evoke the same deep emotions in people with my art as I felt with theirs. I had actually tried to do this long before in Slovakia, but I was confronted with misunderstanding and even ridicule, after which I shut down as a performer. The environment of Berlin's queer clubs helped me to open up again. It was radical.

What kind of care do you need alone after an intense performance or installation?

I am an introvert, so any strong experience that I directly share with people is intense for me and I need to spend time alone after it. Solitude is healing for me. I love my community, but socializing before or after a performance or at an opening is very draining for me. In the past, I haven't protected myself enough. I gave myself away too much and didn't think about my mental health. I'm at a time in my life where I'm trying to set new boundaries and conditioning in which I want and can work and collaborate. I'm trying to remember that my art is there for everyone, but not me.

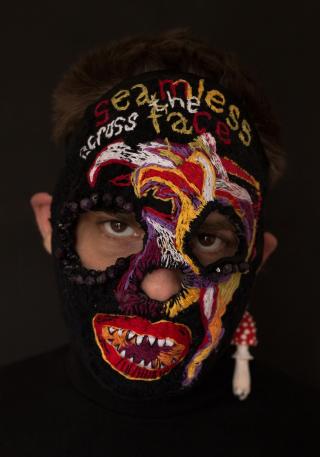

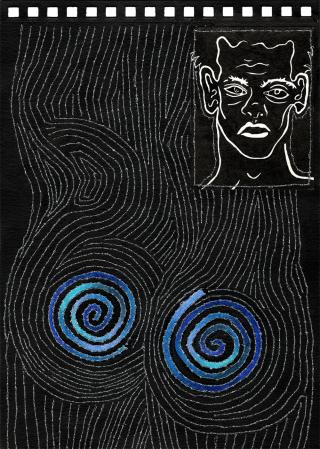

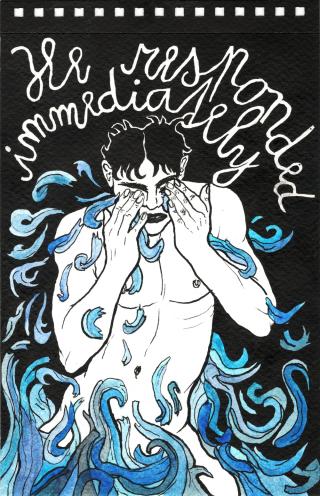

In the title of the piece, Cute & Tragic, you refer to a feature of bipolar disorder that you worked through with hand embroidery. Have you thought of another medium of processing? And why did textiles win out in the end?

I process themes and phenomena related to mental health in most of my work. I grew up in a society where the topic of mental health was constantly stigmatized and vulgarized. It was during the creation of Cute & Tragic that I promised myself that I would use every media opportunity and platform offered to me to sensitise myself to these themes. For me, hand embroidery is not only the medium I have chosen for visual treatment. It is a survival strategy for me - a healing and meditative process where I can truly relax and get in touch with my emotions. When creating Cute & Tragic, I initially thought of a much more spectacular execution - I wanted to make a narrative film with original costumes, music and set design. My ideas are often spectacular, but the budget I'm working with so far is limited. However, I can embroider at home in bed or on the train, piecing small details together to create something truly epic. That's why embroidery and working with textiles remains a medium I like to reach for often.

In recent years you've set boundaries of intimacy. Can you remember a specific moment when you said that you really needed to do that for your sanity anymore?

It was mostly about boundaries in relationships with other people, but also about my relationship with my work, art and the art community. A few years ago I started seeing a psychotherapist regularly more or less out of curiosity, because I wanted to understand more deeply some of the feelings I talk about in my work. I realized that the way I was working was no longer sustainable and the frustration within me escalated. At the end of 2023, after opening my biggest solo exhibition to date and also publishing my first monograph, I burnt out. I thought I would never create again. I lost many ideals and started to look at the world more realistically, which was really painful for me. It took me over a year and a half before I could even begin to think about wanting to create again. I'm trying to do everything I can not to go back to that place.

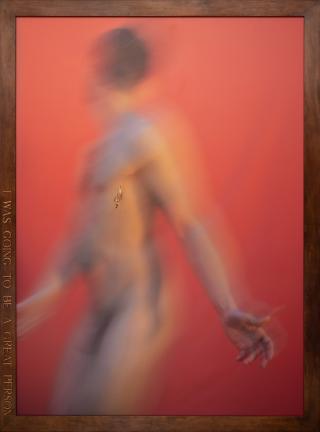

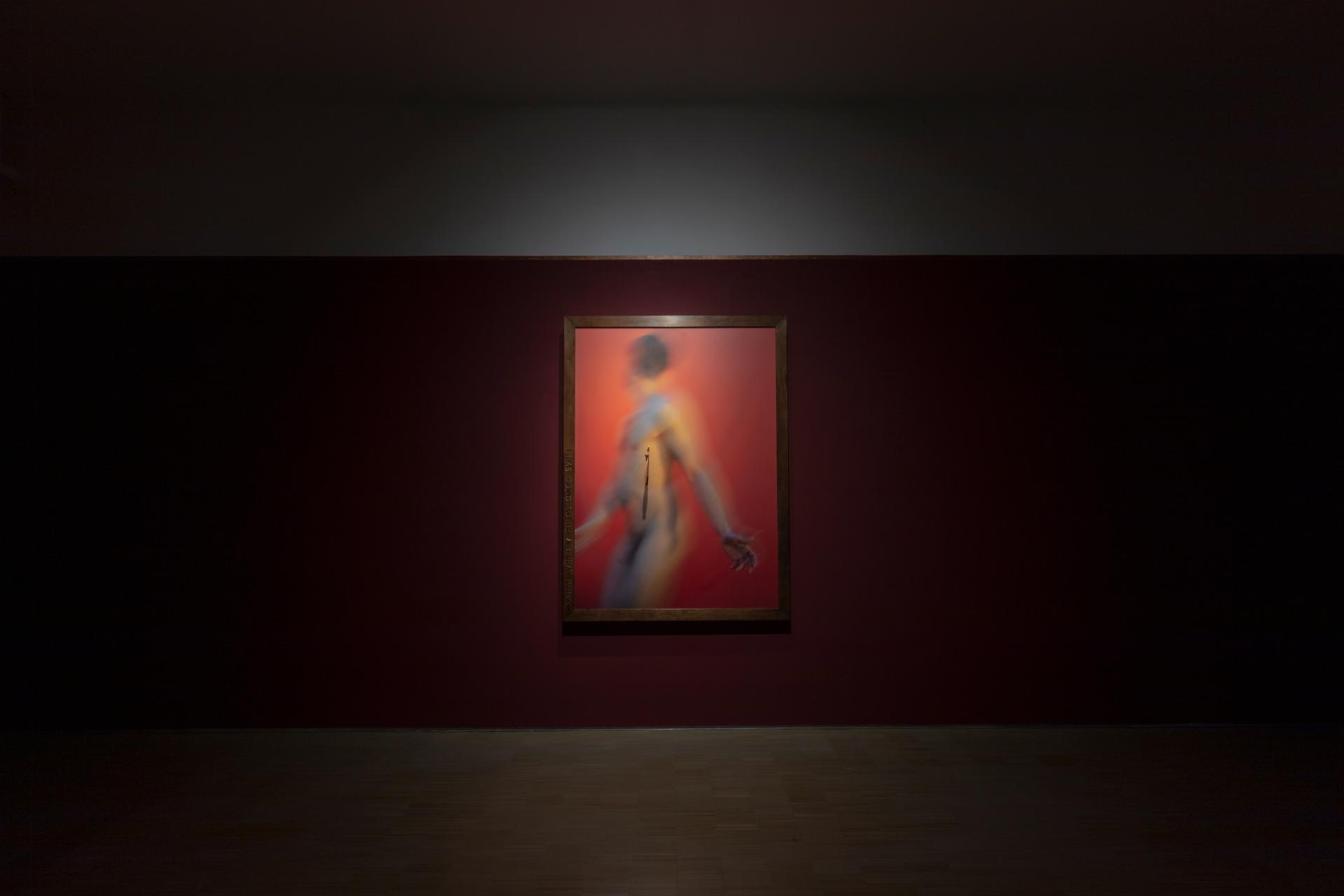

I Was Going To Be A Great Person is a memorial to Juraj and Matúš, who were victims of the terrorist attack in the Bratislava LGBT café Tepláreň. What exactly did this moment trigger in you - and how did you decide on the visual language of the commemorative "image"?

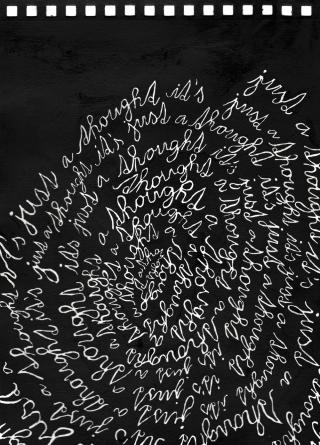

It triggered a deep sadness in me, of course. In retrospect, I guess I could say that this terrible event made me want to tell more and more about the lives, stories, love and suffering of queer people in my work. I can't quite remember why I "chose" this form of work. It's probably going to sound a bit like a cliché, but I often have a kind of vision - in daydreams and at night - during which I often see images or whole complex artworks very specifically. When they seem really good, I try to sketch them immediately in my diary so I don't forget. That's exactly how this piece came to be.

Do you have works that you feel you wouldn't want to sell to any collection?

I've never been a very material person, so I can part with pretty much anything. With some pieces it takes me a while because I've spent a really long time with them, but of course I need to make a living with my work. I also know that in good collections my works will be archived in better conditions than in my warehouse.

When a work "won't go," do you put it away, rewrite it, or let it grow into another medium?

Yes, it's pretty much exactly as you say. I have whole sketchbooks of work I want to create one day, but the time hasn't been right yet. I also have several boxes of various embroidery and fabric elements at home that I'm sure I'll use for something someday. Not to mention an archive of photos. Right now, I am at the stage where I am actively working with this archive and I want to dedicate myself to it during my residency at Telegraph.

You are currently finishing your dissertation at AVU in the New Media 2 studio with Darina Alster. Can you tell us more about the project?

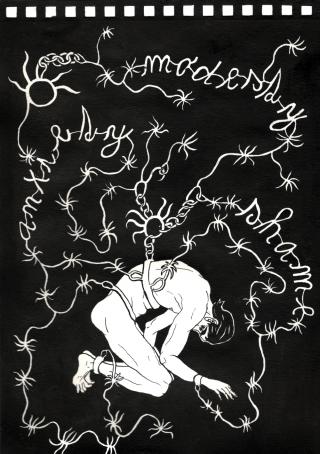

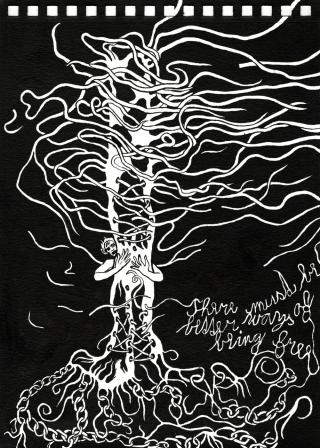

My dissertation project is titled Innerviews: Autotheory, Imagination and Affinities as Strategies of Queer Survival and consists of several artistic research outputs that I have been working on over the past five years. In the theoretical part of the project, I contextualize my own artistic output within queer and feminist theory, and highlight the importance of fantasy and imagination in the lives and artistic practices of queer people. I draw primarily on practices of auto-theory that subvert rigid academic theoretical structures and implement personal experience, corporeality and subjectivity into theory. The term emerged in the early 21st century to define critical literary works in which theory and philosophy are closely intertwined with autobiographical and personal writing. Autotheory is explored in detail in Autotheory as Feminist Practice in Art, Writing, and Criticism by Canadian writer, artist, and curator Lauren Fournier. The main output of my dissertation is the author's book Innerviews, in which I purposefully apply these ideas and practices. Innerviews is a fusion of memoir, novel, and critical-theoretical text in which I convey a personal experience of growing up and discovering one's otherness and identity. I hope to publish the book next year.

Jan Durina is a Slovak interdisciplinary artist based in Prague. He is also co-founder of the performance collective Romeo & Hellion, which he founded in 2020 with Slovak artist Miriam Kardošová. Through performance, photography, and sound, Durina explores the nuances of narrative and addresses themes such as loneliness, loss, the boundaries between body and nature, and the distortions of the human mind as experienced within changing notions of gender and identity. Durina creates multimedia artworks that seamlessly and confidently transition between the contexts of exhibition and performance. His artistic thinking draws on critical queer theory, feminist and ecofeminist thought, and auto-theory. Themes of mental health, human vulnerability, care, collaboration and horizontally functioning interpersonal relationships emerge as essential and recurring elements of his work. Durin's works are part of the permanent collections of the Slovak National Gallery, the Peter Michal Bohúň Gallery in Liptovský Mikuláš, the Benešov Museum of Art and Design, and numerous private collections.