Jakub, your work often explores themes of childhood, socialization, and the subconscious. How do these themes manifest in your contributions to the Game Owner exhibition?

The theme of childhood—or more precisely, the sense of an individual’s uprooting or the misinterpretation of that experience—has accompanied my work for several years. I approach imagery intuitively, layering stories and motifs that often intertwine or repeat. A good example is a series of portraits featuring children with T-shirts pulled over their heads. In this exhibition, the tension between individuality and collectivism is perhaps most evident in the series involving numbers. These feature anonymous figures marked with numerical codes on their skin. The imagery evokes associations with prisoners in forced labour camps, stripped of personal identity and reduced to a sequence of numbers. Such markings could also reference ID numbers or birth registration codes—numbers assigned by external authorities that accompany us throughout our lives.

Your paintings frequently depict anonymous, ritualistic figures. Can you discuss how these representations relate to the broader themes of control and conformity in society?

We live in a time dominated by the cult of the face—through social media, selfies, school portraits, vacation snapshots, ID photos, and more. This trend is strongly reinforced by the internet and digital culture. It seems that visibility has become the primary measure of identity. My anonymized portraits, where the faces are concealed, are a subtle and subversive response to this phenomenon. While art might not be able to change the world outright, it can pose questions, reflect on societal changes, and foster cultural awareness. That, in itself, is a meaningful role.

The Game Owner exhibition juxtaposes your work with Søren Dahlgaard’s interactive sculptures. How do you perceive the dialogue between your introspective, static pieces and his participatory, kinetic works?

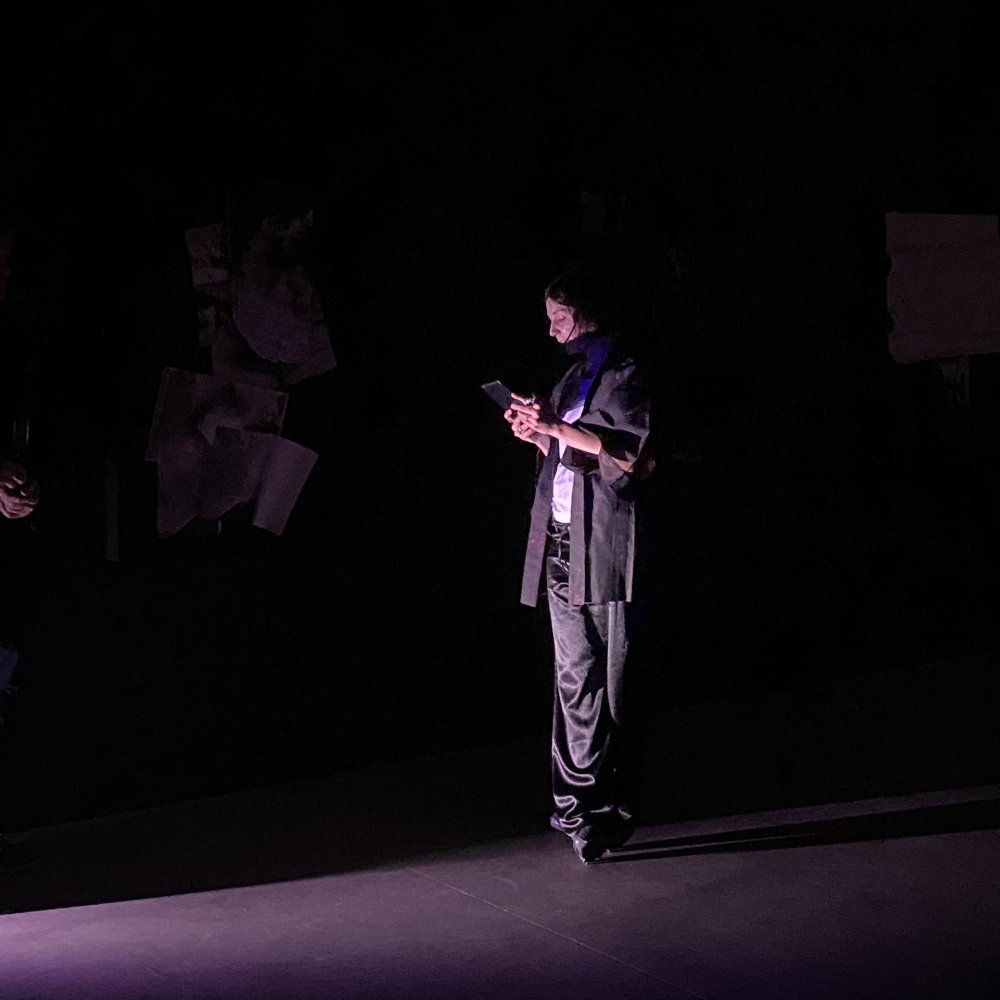

From the beginning, I was looking forward to the dialogue with Søren. Moreover, it seemed important to me that each of us has a unique sense of humor and criticism in our work. Søren’s work is very performative, emphasizing the process of creation and presentation, which sometimes has a form of happenings, which, while it may seem cheerful and playful, carries a weighty content. In some ways, his approach reminds me of the Fluxus movement. I’m particularly reminded of Milan Knížák and his performative piece involving paper swallows being thrown into the Vltava River. In my own practice, irony, exaggeration, and poetic elements serve as vehicles for delivering layered meanings. This shared ability to work with nuance allows our contrasting styles to complement one another.

Your art often employs minimalistic color schemes and symbolic imagery. What role do these elements play in conveying the psychological depth and societal critiques inherent in your work?

For me, freeing myself from detail means not working with a strictly realist, pictorial approach. I don’t need to depict reality in a painting—I just need a fragment, a slice of what feels important to me. I can still use realism to heighten the effect on the viewer. I used to work in a more graphic style, drawing inspiration from the avant-garde and from totalitarian-era prints. My earlier paintings and drawings had the atmosphere of quasi-agitation posters. My use of color was also part of this conceptual approach.

Your work often hovers between the real and the surreal, with imagery that feels dreamlike, uncanny, and psychologically charged. In what ways do you see yourself in dialogue with the surrealist tradition, and how do you adapt it to address contemporary themes?

I deduct elements from my own and partly the collective memories. Certain events in paintings are actually schemes that are built on their own and often shared memories. Surrealism has a deep tradition in the Czech Republic. Artists such as Štýrský, Toyen or Nezval didn’t have an intensive dialogue with Breton and other French surrealists in the interwar period. There were a lot of very interesting authors. But their idea of the painting was a little different. They were based on psychic automatism and their work was very much based on the interpretation of the unconscious and the dream. However, their work often centered around psychic automatism and dream interpretation—deep dives into the unconscious. My own approach is more conscious and deliberate. I’d say my aesthetic and conceptual inclinations align more closely with symbolism, magical realism and even post-expressionism.

That’s a helpful distinction. I can see how your approach departs from traditional surrealism, even as it shares certain visual strategies. Given your personal history, how has the cultural and psychological shift following the fall of the Iron Curtain shaped your artistic language?

I was still a child during the Velvet Revolution in 1989. In our small town, the structures of socialism lingered well into the mid-1990s. Gradually, Western consumer culture began to seep in—brands like McDonald’s, Nike, Adidas, and products like Kinder Surprise and Sony electronics appeared, often in strange juxtaposition to the older social landscape. This created bizarre overlaps—a kind of cultural vacuum. For instance, my school was renamed from Lenin Primary School to Seifert Primary School but nothing else changed. I remember the same plastic tablecloths in the cafeteria, the same teapots, and the same worn school desks my mother had used in the 1970s. These remnants became symbols of a suspended time. Perhaps that’s why my paintings awake a sense of temporal dislocation. They resonate with people who lived through that era—offering a kind of shared memory space, half-forgotten yet emotionally present.

Much of your imagery seems to reflect a world caught between memory and distortion, order and chaos. Do you see your use of automatized figures as a response to the collective psyche shaped by post-totalitarian societies?

I think that in a post-totalitarian society this kind of expression resonates more urgently. Perhaps out of a well-known feeling of disenfranchisement and the desire of the individual to resist it. At its core, my work engages with humanity’s timeless struggle for survival, for meaning, for the essence of existence. But there’s also a spiritual dimension—a quest for inner order and guiding principles without which one cannot live.

Looking beyond the Game Owner exhibition, what themes or concepts are you currently exploring, and how do you envision these evolving in your future projects?

That’s a good question. I’d like to continue my artistic work across the media. Perhaps with more emphasis on the installation and the object. I have for example for a long time been thinking about putting my sculptures in a public space.