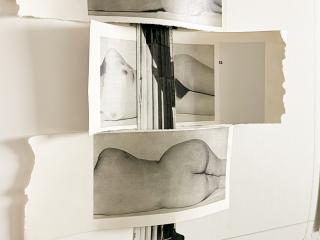

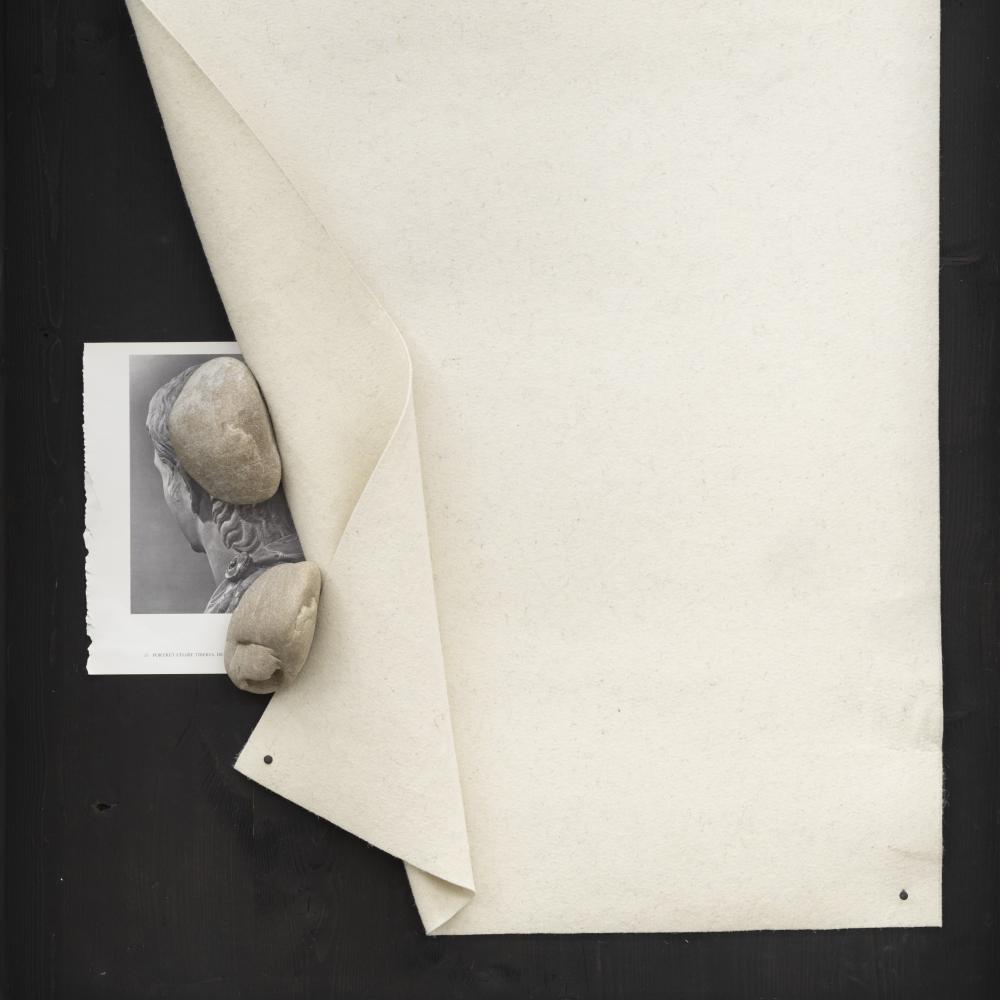

The first encounter is never neutral. Standing before one of Lucia Tallová’s dense constellations of photographs, found objects, and painted surfaces, the gaze hesitates. Where to begin? Which surface holds the key? The work opens not with a declaration but with a delay, a temporal suspension. One might call it the dramaturgy of hesitation: Tallová’s practice disarms the appetite for immediate recognition, redirecting the eye toward fragments that refuse to be sutured into a stable whole. This act of withholding is crucial. It is how she transforms the detritus of memory into an architecture of longing.

When Till Fellrath and I invited her to participate in the Lyon Biennale in 2022 under the title Manifesto of Fragility, it was this capacity to stage fragility not as weakness but as structural principle that drew us in. Her assemblages neither monumentalize ruins nor sentimentalize them. Instead, they expose fragility as the ground condition of both objects and subjects — a condition that resists closure. Her contribution then seemed to extend the Biennale’s thesis: that fragility, far from being a deficit, is the very site where histories remain open to re-inscription.

Within a wider art-historical lineage, Tallová’s practice resonates with Surrealist strategies of collage and assemblage, but without their fetish for the unconscious. Joseph Cornell’s boxes hover as a precedent: intimate theatres of memory, built from the residue of a life lived elsewhere. And yet Cornell’s work tends toward the whimsical, while Tallová’s domestic lexicon of photographs, furniture fragments, and glass domes is suffused with melancholy. One might also place her alongside Louise Bourgeois, whose “cells” turned fragments of furniture and fabric into architectures of affect. In Tallová’s hands, however, the fragment becomes less an enclosure than a threshold — a hinge between memory and forgetting.

Her landscapes of ruin also recall Anselm Kiefer’s monumental canvases, where the debris of history threatens to engulf the present. But Tallová operates on a different scale. If Kiefer monumentalizes ruins to stage the drama of collective memory, Tallová miniaturizes them, insisting on the intimacy of loss. Likewise, Doris Salcedo’s scarred furniture pieces, borne from Colombian histories of violence, provide a comparative frame: both artists transform the domestic object into testimony. Yet Tallová’s mode of testimony is less juridical than lyrical. It whispers rather than declares.

This global dialogue matters because Tallová belongs to no provincial idiom. Her work articulates a form of memory-making that is legible across geographies: an art of the fragment that resists the authoritarian closure of narrative. In this sense she aligns with what Walter Benjamin once called the “dialectical image,” where fragments from disparate times collide to produce flashes of historical insight. Her practice can also be read against Rosalind Krauss’s theorization of the “expanded field” of sculpture, in which the boundaries between architecture, landscape, and object collapse — though Tallová inflects this collapse with a distinctly affective and mnemonic charge.

More recently, critics such as Hal Foster and Benjamin Buchloh have argued for the fragment as a recurring modernist strategy, a way to resist totalizing systems of meaning. Tallová extends this lineage into the twenty-first century, but with a difference: her fragments are not abstractions of modernity, but the tactile residues of lived lives. They embody what Svetlana Boym would call “reflective nostalgia” — not the desire to reconstruct the past, but the act of lingering with its incompletion. Still, Tallová’s practice emerges from a specific geography: Central and Eastern Europe, a landscape shaped by the collapse of communism and the ongoing archaeology of its ruins. The flea market and the second-hand shop — sites where she discovers her objects — are not neutral reservoirs. They are the informal museums of a region where the circulation of fragments testifies to the discontinuities of history.

To encounter these objects is to face not simply the patina of time but the violence of dispossession. A photograph without context, a piece of furniture without origin, a fragment stripped of its domestic sphere — each bears the scars of interrupted lives. In this sense, Tallová stages not merely the memory of objects but the condition of a society where memory itself is unstable, fractured, suspended between regimes.

Eastern European artists across generations have grappled with this condition. Magdalena Abakanowicz’s fiber environments, woven from rough sisal and hemp, spoke of bodies and histories torn yet enduring. Mirosław Bałka’s installations, made of soap, ash, or concrete, transformed everyday matter into vessels of memory, saturated with Poland’s histories of trauma. Jiří Kovanda’s subtle actions in 1970s Prague made fragility itself into a political gesture, a way of resisting the monumental spectacle of power. Geta Brătescu, in Romania, assembled fragile collages and textiles as counter-histories to official ideology, while Sanja Iveković, in Croatia, turned domestic materials into feminist interventions against patriarchal and nationalist structures.

Art historians and critics such as Piotr Piotrowski and Boris Groys have argued that Central and Eastern European art after 1989 should not be read as derivative of Western paradigms, but as articulating a “horizontal art history,” one that foregrounds its own temporalities, discontinuities, and cultural vocabularies. Tallová’s practice belongs firmly in this lineage. Her fragments are not relics salvaged for nostalgia but active participants in what Piotrowski called the “critical museum of memory” — spaces where the detritus of everyday life acquires the force of historical testimony. Boym’s notion of “ruins of the unfinished” becomes, in her hands, not just a metaphor but a method: a way of building environments where the incompletion of history is not hidden but staged.

What distinguishes Tallová is the texture of her fragments. Photographs, furniture, glass domes — these are not neutral materials but gendered signifiers of the feminine interior. In repurposing them, she enacts a counter-archive of domesticity. Against the masculinized rhetoric of ruin — of wars, empires, monumental collapse — Tallová constructs fragile architectures where the very materials of care and intimacy become monumental.

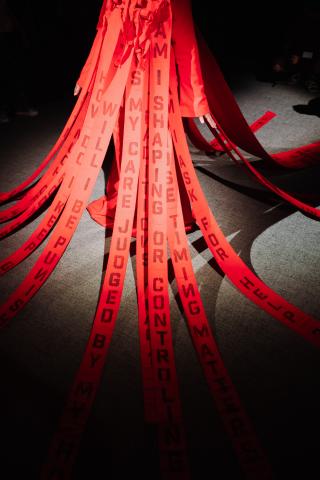

Her title, I Wish That I Was Made of Stone, makes this tension explicit. Stone suggests permanence, endurance, the monumental. But Tallová’s assemblages are anything but stone: they are fragile, ephemeral, perishable. The wish to be made of stone is thus not fulfilled but displaced. It reveals the paradox of yearning for stability while inhabiting fragility.

In this sense, her work resonates with Baldwin’s insistence that vulnerability is not weakness but the ground of relation. To yearn for stone while working with what is fragile is to inhabit the contradiction of being human: desiring permanence while knowing that only fragility tells the truth.

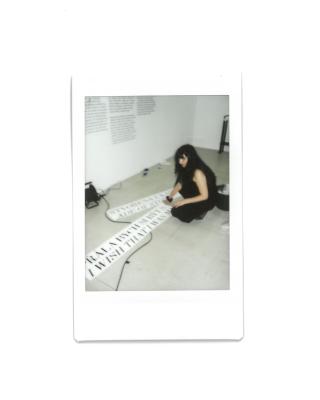

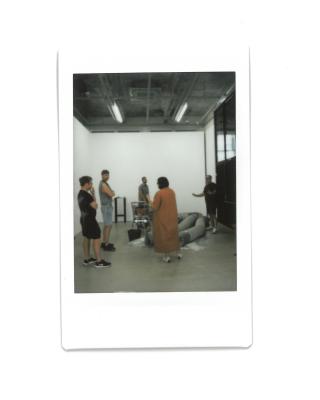

Telegraph Gallery in Olomouc, with its 350 square metres of generous space, has allowed Tallová to expand her practice into a fully immersive environment. Here, collage, object, sculpture, and painting do not appear as separate media but as elements of a total installation. The gallery becomes a “theatre of memory,” where viewers are not spectators but participants in an architecture of fragments.

The site-specificity matters. Unlike the vitrines of a museum, where objects are immobilized, here the fragment regains its performative capacity. Arranged in constellations that suggest both ruin and stage-set, Tallová’s objects resist museological stasis. They are not relics but actors. The viewer becomes implicated in their performance: walking among them, one feels the pull of memory as an affective environment rather than an epistemic claim.

This is not nostalgia. It is not an attempt to restore a lost whole. Rather, it is what Fred Moten might call “the surround” — an aesthetic condition where fragments create a space of encounter that exceeds representation. Tallová’s installation suspends us in this surround, where meaning is less a fixed proposition than a resonance one inhabits.

To write of Tallová is to write of thresholds: between fragment and whole, memory and forgetting, fragility and permanence. Her work reminds us that ruins are not mere residues but generative spaces, where history remains open, unsealed. In I Wish That I Was Made of Stone, she stages the paradox of desiring the permanence of stone while working with the ephemerality of paper, photograph, fragment.

And perhaps this is where Tallová’s work speaks most urgently to our time. In an age that promises endless preservation — digital archives, cloud storage, algorithmic memory — her fragments refuse the fantasy of permanence. They remind us that forgetting is not failure, but condition. That to live with memory is also to live with its erosion. Julia Kristeva once wrote that memory is inseparable from its lapses, that it is “always already perforated by absence.” Tallová makes this perforation visible, not as a lack but as form. Each fragment is a wound that insists on being looked at, not sutured shut. Her dramaturgy of hesitation calls us to stay in the tear, to inhabit the moment when what we thought was whole begins to come apart. And this insistence matters: it resists the contemporary seduction of smoothness, of the archive without gaps, the story without contradiction, the surface without crack. In Tallová’s work, the fragment is not evidence of incompleteness but a declaration that completeness is a fiction. To dwell in the fragment is to accept that what slips away is as formative as what remains. It is to see that erosion is not the enemy of memory but its pulse.

Tallová’s work insists on this incompletion. It tells us: to endure is not to be stone, but to remain fragile, permeable, open. In a world that seeks monuments, she offers us ruins. In a culture that demands certainty, she gives us hesitation. And in that hesitation lies the truth: that fragility is not the end of things, but their beginning.

Sam Bardaouil

Director of Hamburger Bahnhof - Contemporary Art National Gallery