Lucia, I will start with a very practical question. How does a graduate of a purely painting studio – you studied under Professor Ivan Csudai – become an artist who works with such a wide spectrum of expressive language?

Paradoxically, I chose Ivan Csudai’s studio precisely because of its focus on painting without overlaps into other media, which I am currently involved in. For me, it was the right studio at the right time. With great concentration I devoted myself solely to painting, not only during my studies at the Academy of Fine Arts and Design in Bratislava, but also for a few years afterwards. It was only during my independent creative practice that I realized how much working with a single technique restricted me.

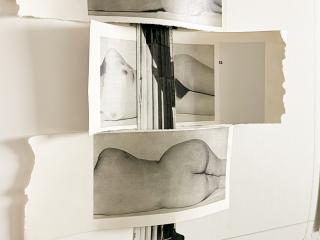

Subtle painterly interventions in old found photographs quickly became three-dimensional relief collages and assemblages. These gradually grew in volume until they developed into sculptural and spatial work. I think this process was intuitive and consequential. It took several years for my work to take on its current intermedial form. In my works I combine various media, materials and forms – from painting and collage to objects and installations. I try to conceive of exhibition projects as a whole, an environment where none of the mentioned media stands alone but complements the others. One work complements another.

Classical painting is often “liberated” from the wall and enters the space, as can also be seen at the exhibition at the Telegraph Gallery. The painting with monumental dimensions of 3 × 6 metres is placed on wooden structures in the middle of the installation, allowing viewers to walk around it and see the exposed back of the canvas. Because of the scale of the work and its very placement, visitors feel somewhat different than when looking at a painting hung traditionally on a wall. I seek to disrupt the usual situation we are accustomed to when perceiving painting.

From my perspective, painting and thinking about painting still remain the dominant part of my practice. When I prepare a technical solution for an object or sculptural outputs, I very often reach for materials and technologies used in painting. I intervene in appropriated materials and objects using paint. Thinking in painterly language feels most natural to me.

And, just for the record, at secondary school I studied stone sculpture at the School of Applied Arts in Bratislava, so I guess sculpture was hidden somewhere in my DNA.

In the text I wrote about your exhibition at the Telegraph Gallery, I focus mainly on the material nature and essence of the objects you work with. It is about the principle of their rediscovery; one could say reincarnation. You yourself, however, also accentuate corporeality and proportionality. It is not present exclusively, but it forms a certain solid framework that shapes a significant part of your work. What is your mental “key” to this approach?

In painting I have long devoted myself to landscapes and spaces without the presence of a human being. I paint abstracted sceneries where the human figure appears only in hints, if at all. Working with old photographs brought, among other qualities, completely new themes, and one of the impulses was the return to the human figure and portraiture. The first collages arose from wedding cabinet cards and family photo albums, from figurative snapshots. Perhaps this is my subconscious way of compensating the absence of people in my paintings. The major themes are memory, forgetting, the transformation of memories, the passage of time and its effect on human beings. In some works, I explore these themes through figurative motifs. The body becomes the bearer or record and remnant of memory.

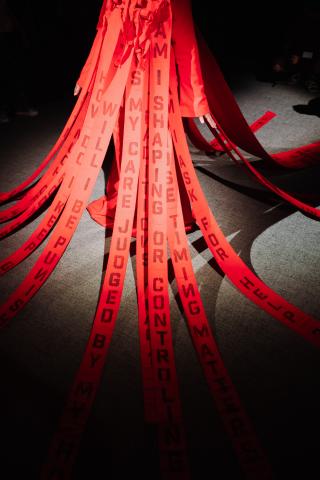

Human figures in my compositions are connected with architectural elements in absurd relationships and illogical proportions. The change of scale between figure and architecture emphasises the impact of human beings on the environment and on the society of which they are part. A person transforms into ruins, into fragments of broken columns, or stands within the foundations of buildings. I rediscover ancient civilisations and build utopian worlds that again succumb to destruction. After many unsuccessful attempts throughout history, these unstable structures collapse. Human existence is predestined to perish. It seems to have lost the ability to function within the current system and the dystopian vision of the future. The body succumbs to time, to ageing and finitude. My works from the Unstable Monuments series attempt to reverse this cycle. I preserve physical vessels and transform them into sculptures or monuments. They become fossils of history, imprints of memories. I also refer to the theme of corporeality in works of a more personal nature – through the view of the female body and the demands placed on it. Physicality, intimacy and vulnerability lead towards questions of identity. Historically, the female body has been perceived more as an object than as the subject of its own story. It bears traces of pressure, deformation, and constant efforts to conform to a defined norm.

Your question mentions the word proportionality, and that leads me to reflections on space and the physical presence of the human being, on the viewer’s entry into my installations. When composing them in space, the scale of the human figure and its contact with the work, the relationship to the formats and dimensions of individual elements, as well as movement and navigation itself, play an important role. The architecture of the installation responds not only to the specific exhibition interior or represented themes, but above all to the viewer. I create an experience that is physical and active. Visitors walk around barriers, pass by wooden structures, climb stairs, or sit on platforms. Through this movement, they change the composition – overlapping and uncovering layers. The change of perspective, from the overall view to a focus on detail, allows them to discover the connections that arise between individual works.

Another question is also related to corporeality. In interviews about your work, you mention female identity and feminism. This topic naturally has many forms and facets, and it has been evolving in recent years. What do these topics mean to you specifically?

The female aspect plays a fundamental role in my work. I express myself on topics that influence me and are essential to me – whether it is female identity, personal and social history, or the country I come from. I dissolve reality in my works through personal experience, and therefore they naturally reflect my attitudes and views on current events from a female perspective. Collages and assemblages often depict a female figure or portrait, with the woman becoming the main character of the story with whom I identify. I draw on historical materials and visual references from different periods associated with the female world. By intervening in them I add a contemporary commentary and compare the position of women in the past with the situation in the 21st century.

Some depictions of women I combine with fragments of wooden furniture – with gentle irony I point out that the woman is perceived only as an accessory to the interior or as a permanent part of the household, unable to make decisions about themselves or their time. She is loaded with all the household chores and the never-ending routine of caring for others.

In the series Fragility of Caryatid, I transform female figures into supportive parts of crumbling architecture. Female figures balancing in complicated poses symbolise the anonymous woman who supports the system in the same way as caryatids support ancient temples. The figures strive with all their strength to maintain balance and not succumb to the burden of duties and expectations imposed on them by society.

In my works I often thematise female corporeality and the tradition of depicting the body – naked, exposed to gazes, defenceless, beautiful, with porcelain skin. I reshape and disrupt the cult of beauty with a personal layer and commentary. I seek to point out the stereotypes that have long influenced the social position of women. The dogmatic approach to the body, especially the female body, reduces it to an object of evaluation, control or modification.

You are very active especially outside the Czech and Slovak environment. You work with galleries in Germany or France. Your language is not entirely “local”; you choose media that are not so highly valued here. Do you perceive any fundamental difference between the art scene, the market and collectors in the Czech Republic or Slovakia and those in Germany, Austria or France?

My main intention is to create freely and authentically. This creative process does not stem from external expectations. It is not shaped by market demands or by my position on the international scene. However, when preparing exhibitions abroad, I naturally take into account the context of the country where I am realising the project – its cultural specifics, audience, and the exhibition space. I strive to make the work communicate with its surroundings, but at the same time I don’t want these circumstances to limit the creative process itself, the choice of themes, or the way they are treated.

Visual art is in a certain sense universal; no translation or explanation is needed. It has the capacity to captivate at first sight. I am still surprised and at the same time pleased by how easily someone on the other side of the planet can empathise with my work. Perhaps it is precisely the fragility and sensitivity that create a connection between me and the foreign viewer. Of course, a piece of art can be understood on several levels. For example, visitors at an exhibition in New York or Tokyo will probably not recognise that I used a page from a book about the High Tatra Mountains, which refers to the theme of my home and the country I come from, and may not be familiar with our current socio-political situation. However, they will gain a different connotation, in which the rock becomes a symbol of eternity, resilience or the layering of time. This level of meaning is more important to me.

As for the art market and contact with collectors, I do perceive differences, especially regarding interest in particular media. In our local environment, collectors are more conservative and prefer paintings. Abroad, on the other hand, collecting institutions as well as private collections are more open and daring. The strongest interest in objets trouvés has been shown by collectors in France, Italy and the USA. This is connected not only to the visual expression of my works but also to artistic tendencies in those countries and the tradition of collecting artists from movements such as Arte Povera or Fluxus. Collectors do not shy away from more complicated acquisitions, which are demanding not only in presentation but also in preservation and storage.

Artists are often said to see the world and events in it through a different lens and to respond to them with a different sensitivity than people who do not create art. Do you see yourself that way? Is it an advantage, or rather an imaginary curse that drives artists further and further, often into dead ends, uncertainty, and aimless searching?

Art should develop critical thinking, support diversity, and help in processing not only personal but also collective traumas. It creates space for reflecting on history, holds up a mirror to society, and can articulate what often remains unspoken or suppressed. Creation is a demanding and unpredictable process. It brings uncertainty and fear of misunderstanding, rejection or failure. In my eyes all authors who reveal their inner world are very courageous. For me, creation is a form of searching and discovering. Sometimes it takes years before one finds one’s artistic language and themes that touch one deeply. I consider fragility and sensitivity to be my strongest qualities. In my work uncertainty and ambiguity appear naturally – not as a mistake, but as part of the process. Our vulnerability is not a weakness. On the contrary, it is a source of sincerity and strength.