The interview with Italian artist Giacomo Modolo took place during his residency at Telegraph, which lasted from July to August. During this residency, we had the opportunity to talk to him about his work, his experiences during his time at Telegraph, and his future projects.

During your stay at Telegraph, you mentioned that you see painting as a kind of diary entry. How do you document what’s happening around you, and which moments interest you the most?

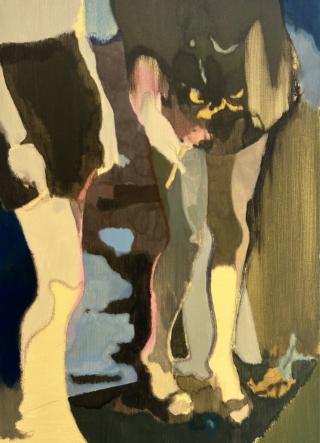

I made one painting every two days, almost like writing pages in a diary. It was my way to set some boundaries—both in time and in space—during a one-month residency. I wasn’t trying to create something spectacular. Instead, I wanted to collect small, curious things—like fragments, different notes that don’t necessarily connect. Most of these came from what I saw in Prague and Olomouc. I even used my insomnia as a chance to wander around and discover the atmosphere of the cities early in the morning.

Can you describe how the Telegraph space and the city of Olomouc influenced you? And which elements of the local environment made their way into your work?

The places where I work always affect me deeply—they change me and my painting. In Olomouc, the first thing that struck me was the mix of architecture and nature. That fit right into my work, which already balances gesture and geometry, figuration and abstraction. For the subjects, I combined photos I took myself with images from books and posters. In this series, I wanted to create a mood of solitude and ambiguity—somewhere between reality and a hallucinatory vision.

In your paintings, you often work with nocturnal atmospheres. What makes the night so inspiring for you?

Things and places take on a different, less objective value. They mix together and create new, unexpected forms. I imagine stories that have just happened, with characters who are sometimes people I know, and other times just faces from a film or even an album cover. In this space, everything blends without clear references—without a specific time or place.

The series you created during your residency is titled This Is No Time for Heroes. What does it mean to you personally?

It's a time when I prefer to observe, focusing on details, rather than on everyday reality, which seems to demand we always be the centre of attention. In the past, I often sought excess in painting, but that period, the little things matter more. For example, faced with the certainty of public opinion, I prefer to champion contradictions and fragile intentions. The idea of the sinner excites me more than that of the hero.

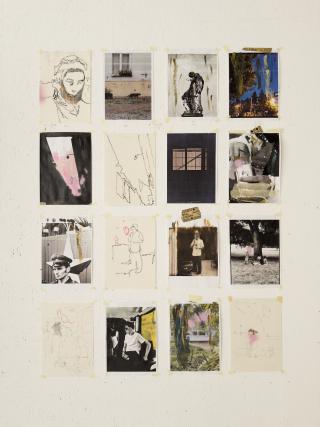

In the preparatory phase of your paintings, you use both your own and found photographs. How do you work with these materials, and what qualities must a photograph have for you to translate it into the medium of painting?

Some of the subjects I paint are ordinary people, others have an iconic or even historical character. What I try to do is build a pictorial story that transforms their identity and puts them in dialogue. To do this, I print the images and work over them, erasing or emphasizing certain details—usually the silhouettes of bodies or objects. Then I redraw a synthesis of them on canvas, sometimes using a projector, so I can keep that film-like quality that lingers in the painting like a shadow.

My use of photography goes back to my early days at the academy, when I was drawn to collage and the aesthetics of punk album covers—a kind of fascination, almost a fetish, for the reproduced image.

What would you like your paintings to share with the viewer? What should the viewer take away from the encounter with your work?

Right now, I think it’s important not to give people a concrete answer about what they’re looking at. Sometimes they recognize themselves in it, because they see something connected to their own experience—and that’s a beautiful thing.

We live in a visual age, where thousands of images bombard us daily. How do you see the role of painting in a world oversaturated with visual stimuli?

That’s the point: painting and photography can have the power to remain incomprehensible; unlike all the answers we constantly get from our devices. Even the most bizarre image made by artificial intelligence is still the product of a fixed algorithm. Maybe painting keeps that human variable of mystery, something complex and sometimes elusive. So, I don’t think we need more spectacle, but more introspection—what happens around us is already shocking enough.

You had the chance to absorb some of the artistic atmosphere in the Czech Republic. Do you notice any differences in the choice of themes or visual language between the Czech and Italian art scenes?

I like the spirit you can feel in Czechia, it’s electric and people are very passionate. It’s interesting to discover such a diverse painting scene, because it seems to me that artists are quite free from movements or trends. Some friends told me about a period of great momentum, and you can sense it in the serious and professional attitude of both artists and people working in the field. I feel there is a strong interest in art to search for an identity but starting from the different experiences of individuality.

You are represented by Crag Gallery in Turin, led by Karin Reis. What projects are you planning together in the near future?

Besides some interesting group exhibitions in Italy, right now we are also working on a book that will collect my painting from recent years. It will include texts by curators and journalists I’ve had the chance to exchange ideas with, who have contributed to my artistic and intellectual growth.